Carpe Diem

Lisa Fraser offers practical tips on how to avoid one of the saddest forms of waste – ‘killing’ time.

I remember the summer holidays when I was a child, when the afternoon in the park felt endless, when I had a sense of infinity … just me, the sun, the heat, and the gift of time.

Yet now as an adult, though objectively I cannot complain about not having free time (in England, employees have weekends, and a generous amount of annual leave), free time feels so rare! I’m always rushing between friends and commitments. I feel I never have time to … enjoy the gift of free time.

To make matters worse, experts have reported how the pandemic has made us more ‘time-confused’ than ever. When I refer to the time before lockdown, I find it difficult to appreciate it was only two or three years ago. The pre-pandemic world seems a lifetime away.

Clocks and calendars measure the biological time, or the ‘objective time’, as the philosopher Henri Bergson put it. But our perception of time can shift, stretch or contract like an elastic band.

Time is, in many ways, a private matter; it’s influenced by our feelings, moods and life circumstances.

Bergson called this aspect ‘duration’ (durée): it’s time as we experience it and represent it in our mind (‘lived time’).

Scientists have even come up with hypotheses to explain why time accelerates as we grow. Two of them caught my attention.

The first plausible explanation is about proportionality: one year is 10% of the life of a 10-year-old child and 15 to 20% of their conscious memory, but it’s no more than two per cent of the lived experience of a 50-year-old adult. The child has more space to record single moments in their brain, printing ‘more life’ in it every day.

The second hypothesis is about physiological pace. Eye movement and the speed to analyse information slow over time; older people are therefore supposed to have less ability to record memories, and time disappears without being noticed. Conversely, children’s hearts beat faster, they receive more stimuli, perhaps giving them the impression that there is more life in their life.

While I enjoyed reading these studies on time elasticity and biological factors, it would be depressing to think we’re condemned to blink and wake up when it’s too late. It’s important to look at the psychological elements as well.

When I look around me, and observe my own life, I see how packed days can be: the constant juggling of multiple responsibilities.

Jugglers don’t have time to think about time: they juggle! When we’re caught in the doing, we have less time to think about our being.

Adult days are also filled with tasks we either perform in autopilot mode or we scarcely think about. Have you ever tried to enjoy the present moment when doing your tax return…?

Sometimes, we don’t think it’s worth paying attention, or we prefer to avoid some reality. We lift up our head, look around, and it’s already night time.

Routine can take over. After the whirlwind of school, uni, first job, we reach a point in life where we feel more rooted, settled. It’s a time when we can notice how time has flown; but also, a time where everything seems more familiar. We don’t need to be as alert as before; we can let our guard down; and perhaps, there is a temptation to notice less.

For children, the world is brand new: they pay attention to everything; they record every single change. Does it add more life to their life? We could consider ‘lived time’ as an ordinary film compared to one in slow-motion. In the slow-motion version (when we’re attentive to our daily life, like little children), each object is physically manipulated in small increments and photographed. But adult age becomes more like an ordinary feature film: time flows.

Our lifestyles can amplify these biological and psychological phenomena. For instance, when we’re sleep-deprived, the brain is less able to record what’s happening around us and we’re less present to the moment. When we’re tired from an illness, we can get out of bed at the end of the afternoon and wonder where our day went. Our body was present, but our mind didn’t record it.

Going back to the metaphor of cinema, the philosopher Gilles Deleuze outlined the difference between a society based on pictures (the image is fixed, still, we can contemplate and print it in our brain) and the introduction of cinema (moving-images, time flows, life is a flux).

From personal experience, a day filled with books feels fuller, and denser, than a day spent in the company of Netflix. I also notice my body more and recognise its needs when I contemplate (reading) than when I am carried in a flow (Netflix).

The moments of ‘flow’ are vital to our mental health: we need to switch off from time to time!

Psychotherapists recommend finding activities which help us forget about ourselves, whether it’s through ironing or playing chess or, best of all, helping others. We need to be able to stop thinking about ourselves and let go of existential worries.

However, disconnecting for too long turns us into zombies! In extreme form, it’s the issue we observe with addictions: getting ‘high’ or ‘out of our mind’ for too long a time damages our personal life, our work life, and our health.

We need to find the right balance between the state of flow and the connection mind/body, rooted in the present moment. The ability to be present to our life, and make the right move at the right time, is also the ability to build a fulfilling life. It is likewise the best way to avoid regrets, and not look back at our life wishing we’d done more with it.

So how do we add more time to our time? How do we create time when we feel swallowed by the tide, or caught in the flow?

Supporting our body and giving it what it needs is surely the first step. Sleeping enough, nourishing our brain and staying hydrated to help it function well are not only healthy habits, they’re also vital for good mental health. They help us be more attentive to the world around us, and increase our ability to record life’s precious moments.

Mindfulness has seen a surge of popularity over the last few years, probably because it can help with many issues, including time awareness. The philosopher Gottfried Leibniz said that time was in essence a series of moments. Mindfulness can help us be more present to these moments.

Prayer in a sense takes us out of time and into the eternity of God. It enables us somehow to stand above the flow of life’s events and look down on them, at least to some extent, from God’s point of view. In that way we are not merely swept along by the flood of activity.

I’ve got into the habit of doing a quick check on myself during the day, at least at mid-day and at the end of the day. I force myself to pay attention to what has been happening so far; how I’m feeling; and I try to notice any need, whether it’s physical (thirst? cold?) or emotional (frustration? lack of peace?).

Each time I commute, I take a one-minute break to stop and notice that I have commuted. It’s based on a belief originating in an Amerindian tribe which says that bodies and souls don’t travel at the same pace, and the body must wait for the soul to catch up when arriving at a destination.

We can also say to ourselves what we’re doing: for instance, I can read; pause for a second and say to myself, “Oh, I’ve been reading for half an hour”. It helps me be more intentional. I realise I am making a conscious decision to read; I am in control of my time. I am the protagonist in my own life. It also adds more being to my doing: my mind and my body are one.

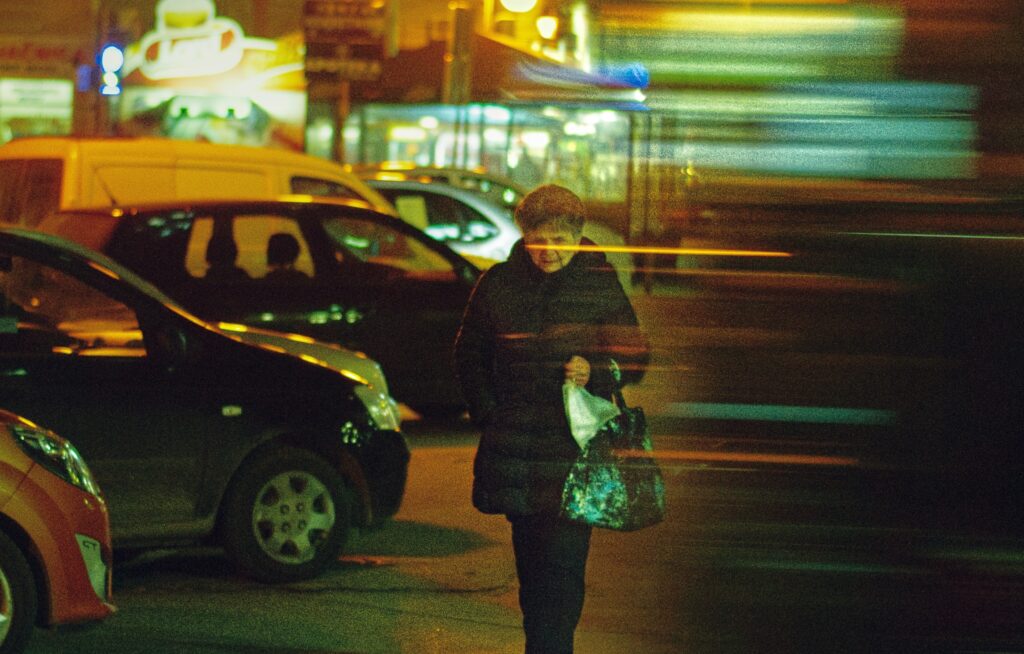

In some cases, noticing the time that passes by can be a conscious decision. For instance, when I take the bus, I can decide to kill time by checking my phone or emails. Or I can make the conscious decision to watch the urban landscape, notice people around me and pay attention to my body.

We can refuse to kill time and decide to use time, or – even better – appreciate time.

Broader lifestyle choices can help us notice – and value – time. When Aristotle said that ‘time does not exist without change’, he implicitly encouraged us to look out for signs of change.

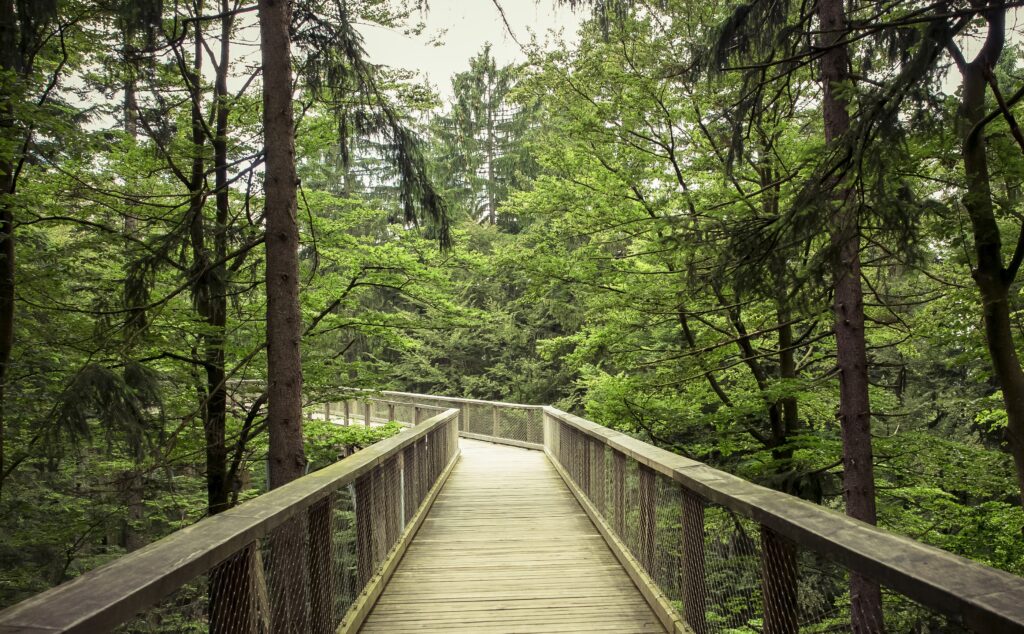

Connecting with the weather and seasons is a good way to do this: for instance, doing the same walk every other day helps us notice seeds growing, flowers blooming, grass drying out in the scorching sun, then withering, and leaves falling from the trees. These experiences are powerfully grounding.

Birthdays are more sensitive. Some people stop celebrating them at a certain age, fearing the weight of time. I’d argue the opposite: celebrating birthdays can help us enjoy time more. Looking back at the year which has passed, and cutting it into smaller chunks, helps see how much we can change in this short period.

Evaluating the recent months often helps us realise we’re more in control, and more capable, than we give ourselves credit for. It helps unfold the year and make it look longer, like stretching an accordion for it to blow out its full melody.

Seasonal celebrations and keeping traditions can also help. We can remember our past self and celebrate our achievements.

The philosopher Martin Heidegger said time is ‘essentially the form of becoming’. When we are confused about our perception of time, there is often a bigger question at play: What am I doing with my days? Am I investing my energy in the right tasks? Am I building something worthwhile? What do I want more of, and less of, in my life?

Overall, taking back control of our time is a call to simplify our lives and focus on what truly matters to us. Reconciling ourselves with time is a call to discern how we really want to live.

It’s about our ability to say no to what is superfluous, make priorities, and focus on what is truly essential. It’s about making space in our minds, and in our lives, for what we want to do, and who we want to be.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Lisa Fraser

Lisa Fraser is a writer for Adamah Media. She has worked as a political Special Adviser, in lobbying and as a consultant, before joining the Civil Service. She loves having long walks, visual arts, and reading books about history and politics.