Pro-life, pro-earth

Authentic feminism means defending life in the womb and the environment, says Rosemary Black.

Ecological destruction and abortion are rarely mentioned in the same breath. Fights against one or the other tend to draw people from opposite ends of the political spectrum. In its caricatured form, ‘leftists’ fight for the environment and generally support abortion, ‘right-wingers’ fight for life in the womb and tend to think ecological concerns are based on fake news.

Those opposing abortion insist they are fighting for life. No-one, they say, has the right to destroy another human life in the name of convenience, no matter how miniscule and invisible this life might be. It is a fight that says we all have a responsibility to uphold the human rights of every person, especially the most fragile, a fight that declares a duty of care toward the most vulnerable and voiceless in human society – the unborn person.

But the other battle being fought also harbours a sincere concern for life, as human and non-human lives are put at risk due to ecological issues like climate change, waste, habitat destruction and pollution.

This is a fight that says nobody has a right to destroy the planet in the name of convenience, a fight that says we all have a responsibility to look after the planet of today and a duty of care for the planet of tomorrow.

And yet, despite their common concern for issues of life, each camp, being so politicised into left and right, naturally distrusts the other.

One side decries individualism, the selfishness which can lead someone to eliminate an unborn child, but its proponents may be blind to the selfishness which can cause untold misery to poor people because of our abuse of the planet. The other abhors greedy behaviour which damages the world’s ecologies, but its followers do not consider that their own sexual choices might be equally egotistical.

Both issues have made waves in recent weeks: the abortion debate is coming into focus as Roe vs Wade, the 1973 ruling which federally legalised abortion up to 24 weeks gestation in the United States, has now been overturned by the Supreme Court. Similarly, as Europe enters into an energy crisis in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, questions of planetary wellbeing and how to effectively move out of fossil fuels are brought to the forefront. The issues are highly emotionally charged, and there is certainly plenty of nastiness on both sides of both debates.

But what if both sides of the spectrum, left and right, instead of being at each other’s throat on these issues, could pull together to build a world in which all life is cared for and can not only survive, but positively thrive?

There would need to be ways of seeing across both issues: as a first-time pregnant mother and a university tutor working across courses with an ecological focus, I have begun to find that the stereotypes of right and left can be dissolved through an exploration of the Feminine – an Archetype which may act as an umbilical cord to connect the two seemingly disparate issues and bring left and right into dialogue.

It works like this: we must rediscover the nature of the Feminine, and we must rediscover the Feminine in nature.

In speaking here of the ‘Archetypal Feminine’, we are not speaking about a particular mother or woman, but are rather exploring a more essential image which sits at the foundation of the human psyche, and even the nature of reality: an image shared not only by women across the world, but by the very fabric of ‘mother nature’ herself. We are asking the question: “What are the essential qualities of femininity?” or perhaps “What gives the Feminine its femininity?”

We find an answer if we look into the womb, that hidden and mysterious place which woman bears within her, but which characterises all that is feminine.

Anatomically speaking, the womb is a mysterious room within the already mysterious place of the female body where a new person comes into being. Philosophically speaking, it is what Plato would have described as chora, the space of becoming, a place between idea and reality, between the immaterial and the material, where ‘word becomes flesh’.

Some scholars have noted that the biblical figure of Mary, the Mother of Jesus, is an ultimate expression of chora, her womb being held as the place where the Word, the logos that is God, became man, flesh: Mary was a hyphen between heaven and earth, between the visible and the invisible.

But every womb bears some element of this expression of ‘becoming manifest’; when a couple says ‘yes’ to each other, with bodies as well as words and vows, this living word is so deep that it sometimes manifests itself as an entirely new human person. The womb is thus a procreative space of becoming, of transformation, and of nurturing life. It is this image that is central to the Archetypal Feminine.

Womb-like imagery is also shared by everything imaging the Feminine Archetype, including the natural world. As woman has seasons throughout her life connected to her womb – years of heightened attractiveness, youth, fertility, motherhood, and eventually the menopause and periods of aging – so too does Mother Earth move seasonally through months of blossoming, those of fruitfulness, harvest, and those of ageing, rest, dying.

This same seasonality is played out on a shorter timescale through woman’s monthly ‘periods’, with days on which she is more fertile, and days on which the womb’s lining dissolves and is lost, as the leaves of Autumn’s trees turn red and fall softly to the ground.

Because of the womb, the feminine is always changing, always in a state of becoming, never finished but always in transition and transformation, always in chora.

The sea, too, shares the cyclical nature that is characteristic of the feminine womb, its winds ever changing, its tides altering with the monthly periods of the moon – that body in space which has always been read through the lens of the feminine. As Peter Kreeft has noted in his lectures, it is no mystery that the poets refer to the sea as ‘her’, with the ships that float upon her usually also named for women.

A ship is a womb in the feminine body of the sea in which man might become an explorer, might, in his quest and voyage, become more who he is – or might get lost upon the storms of the sea, just as he might get lost in love for a woman: a love which calls him further into being, a love which demands he take up new responsibilities, a love which further develops his manhood.

Just as the sea invites man to greatness and ever further exploration, though he can never dominate it and should never try to, so woman (simply for being woman) calls man to become ever more, ever better, for love of her, without ever trying to subjugate her.

The changeability of the Feminine is at times terrifying to man and woman alike, but it is also life-giving and beautiful, and in it we are swept up into becoming more who we most intimately and truly are. “The Word for World is Forest” wrote the great science fiction and fantasy writer Ursula Le Guin in a tale which deals with issues such as colonialism and the environment. I would be so bold as to change this to “The word for world is womb”. The earth participates in the changeable, powerful, life-giving, becoming force that is present in what psychologist Erich Neumann called the Archetype of The Great Mother.

If the word for world is womb, then a term for one of the problems of the world we are living in would be ‘cultural hysteria’, or even ‘cultural hysterectomy’. A medical procedure in which a woman’s womb is removed, usually in response to a cancerous disease, the term ‘hysterectomy’ is rooted in two Greek words: ‘hyster’ meaning womb, and ‘ektemnein,’ meaning to cut out.

Similarly, ‘hysteria’, a word we now use to describe an exaggerated hilarious or emotional response, has the same Greek root and was originally a medical term for a ‘nervous disease’ of the emotions contracted solely by women and attributed to a defect of the womb (claims which were not substantiated as medicine progressed!).

I reappropriate the terms here to describe a hysterical culture: a culture experiencing a nervous disease as a result of, in this case, self-imposed defects of the ‘wider womb’. In our own cultural hysteria, we are self-prescribing cultural hysterectomy: we are a culture that is cutting out its own womb, both at the scale of the planet, and that of the person.

On a planetary scale, we can see these anti-womb sentiments in our forgetfulness of seasonality and our disdain for changeability.

In the name of convenience, we demand strawberries all year around, regardless of the seasons, from countries we don’t know the first thing about. In the name of efficiency, we work the same hours every day regardless of when the sun and moon grace the sky. We wipe out the life-giving womb of the ocean with our propensity for plastics. We waste away the womb of the earth with our landfill. We carelessly extract resources where we ought to let grow. We are all for production, but not for reproduction – and in over-producing, the earth begins to lose her capacity to reproduce, her capacity to bear life.

As farms have a greater and greater turn-over, the earth begins to become barren, requiring greater chemical ‘assistance’ through fertilisers which harm natural surroundings and threaten other species. Irigary and Marder, thoughtful writers on ecological issues, speak of a culture ‘forgetful of life’, for when we are forgetful of the nature of the feminine, nature too forgets her femininity, and Mother Earth loses her ability to bear forth new life.

When we start to see the earth through this lens, we can see that we have been ‘forgetful of life’ not only at a planetary scale but at the scale of the feminine body, which seems to be suffering a deep disdain in the modern world.

Mistaking equality for sameness, and time spent in the workplace as the ultimate measure of gender equality, liberal feminism asks modern woman to reject her womb, her seasonality, her changeability, in short her very body in order to be like man – rather than striving to build a workplace that might work within the delineation of difference.

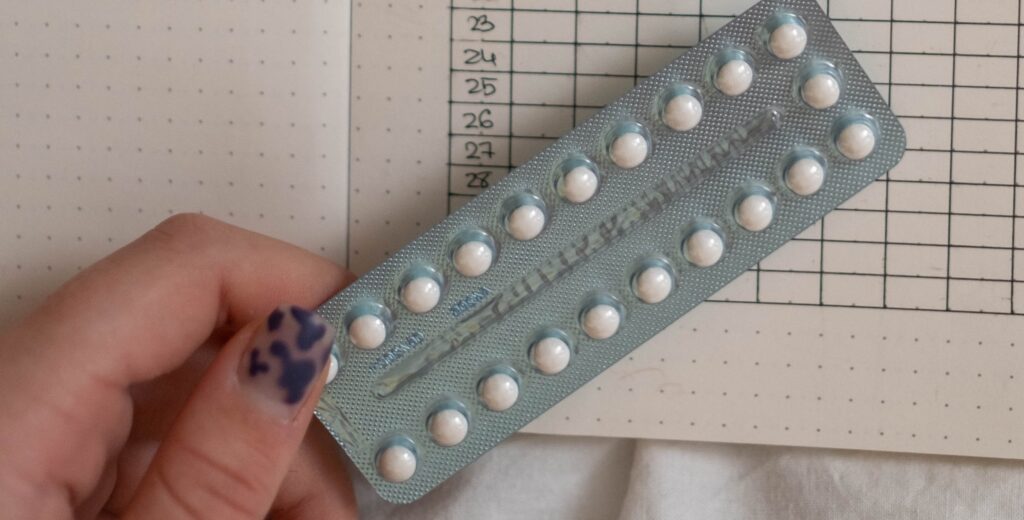

Contraception is the first symptom of this anti-womb sentiment; women are told that to succeed, they must flatten their natural, physiological cycles, working against their fertility and their bodies in order to become more themselves and ‘achieve their dreams’.

The contraceptive mindset affects the monthly seasons as well as the longer seasons of life, as society and social media pressures woman to be ever blossoming and desirable, but never fruitful except 1.8 times and, most of all, never entering the autumnal and wintry sequences of ageing … She must look like a desirable virgin, but actually be regularly sexually active (though deliberately infertile); she must be productive in the workplace but be a reproductive mother only if absolutely necessary – and she must look 22 forever.

The outcome of the contraceptive mindset has not been a deeper acceptance of women in society, but a denigration of fundamental aspects of womanhood. For if we reject the womb’s seasonality, then it follows that we reject the very function of the womb that those seasons foster: the bearing of life, the making room for a being to ‘become’.

Abortion is used where contraception ‘fails’ (and it fails often) because the abortive mindset is naturally borne from the contraceptive mindset. Woman in modernity, in order to ‘become herself,’ must reject herself. Modern woman is in hysteria: society asks that she sacrifice her body and her children in a nervous wager for ‘success’, a wager of production over reproduction in which the womb is viewed as a bodily defect.

In the same way that contraception flattens a woman’s cycle, so environmental carelessness flattens the seasons of the earth. In the same way that chemical contraceptives not only prevent pregnancy in the present but may also harm the woman’s health and her future fertility – so too our chemical and plastic pollution of the ‘womb of the world’ that is the ocean wipes out marine life in a way which will impact our seas and the world for generations to come.

And finally, in the same way that abortion empties the womb and the world of the beauty of human life, so too does extraction of resources, when careless, rob the world of non-human and human life alike. If, as noted above, we want the world to be productive but not reproductive, why are we surprised when we find it becoming both ecologically and demographically barren?

Certainly, just as nature should not be exploited, neither should the woman’s womb.

Woman cannot be merely a baby-producer, subject to man’s whims and lust. We are right to react against these kinds of stereotypes – but in throwing out the stereotype, we must not lose the Archetype with it. We should not go from one bad extreme to another.

Our cultural hysteria is symptomatic of a gnostic culture, one which severs body from soul, dividing whim from concrete consequence, separating word from flesh – for without the wombly chora, there is no space in which the two can come together.

The above-mentioned Luce Irigay, who is especially sensitive to the motherly nature of the earth, writes of earth separated from sky as body separated from soul. This is a powerful image: the body of the earth has been disconnected from the spirit of the sky, as we have forgotten that what we do down here affects what happens up there. The more we rip up and damage the earth without thought, the more the sky suffers, either through holes in the Ozone layer or through being saturated with chemicals.

An affront to the body is an affront to the soul, and the whole being suffers as a result. So too with woman: in acting against her body, her whole being suffers.

The sky has often also been read through the mythological lens of the masculine. Here we see that when we lose the feminine, we lose the masculine also. For as our destruction of the world-wide-womb leaves human and non-human life either dead or endangered, leaves the earth herself scarred, and leaves the sky with gaping holes – so it is that when woman empties herself of the mysteries of the womb, humanity fails to come to its fullness: children are lost, woman is wounded, and man is emptied of his manhood.

Contraception and abortion are not solutions to negative patriarchal structures in the way they are presented – rather, they allow man to take advantage of woman and to reject responsibility for his actions in the sexual sphere, which can be conveniently covered up by contraception and ‘erased’ by abortion. In failing to take up responsibility, men fail to become men, preferring to remain children instead.

Women become men, forced to ape masculine standards of achievement; men become children, and children do not become at all: this is the prognosis of cultural hysterectomy.

Stones have been thrown through the window of the womb like stones through stained glass windows of cathedrals during the Reformation. But in an effort to lose a negative stereotype, a distortion of the archetypal goodness that is in the Feminine, we have unwittingly lost the Archetype itself, just as an appreciation of the Beautiful was thrown out alongside the extravagance that was being criticised by reformers who threw the stones at the glass.

To recover from cultural hysteria, we must restore the window of the womb at every scale, putting the person back into the planet and the planet back into the person, thinking globally and locally, acting in personal conversion as well as aiming for just policies.

Pro-lifers and environmentalists need to sit by the ‘wombly window’ together, letting the coloured light stream in, allowing new understandings to form and new dialogues to take place.

In rediscovering the nature of the feminine, and rediscovering that which is feminine in nature, together we might be able to build a world that fosters life at the scale of the person and of the planet, a world in which children are welcomed and the earth is responsibly stewarded. A culture not forgetting life, but, rather, begetting life.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Rosemary Black

Rosemary Black is a designer, writer, wife, mum and a tutor in Architecture at Edinburgh University, writing from Glasgow where she lives with her family. She has written for the RIBA Journal and other publications, maintaining an interest in stories, faith, architecture, landscape, visual media, education and the points at which they cross over.