When religious values help fight a virus

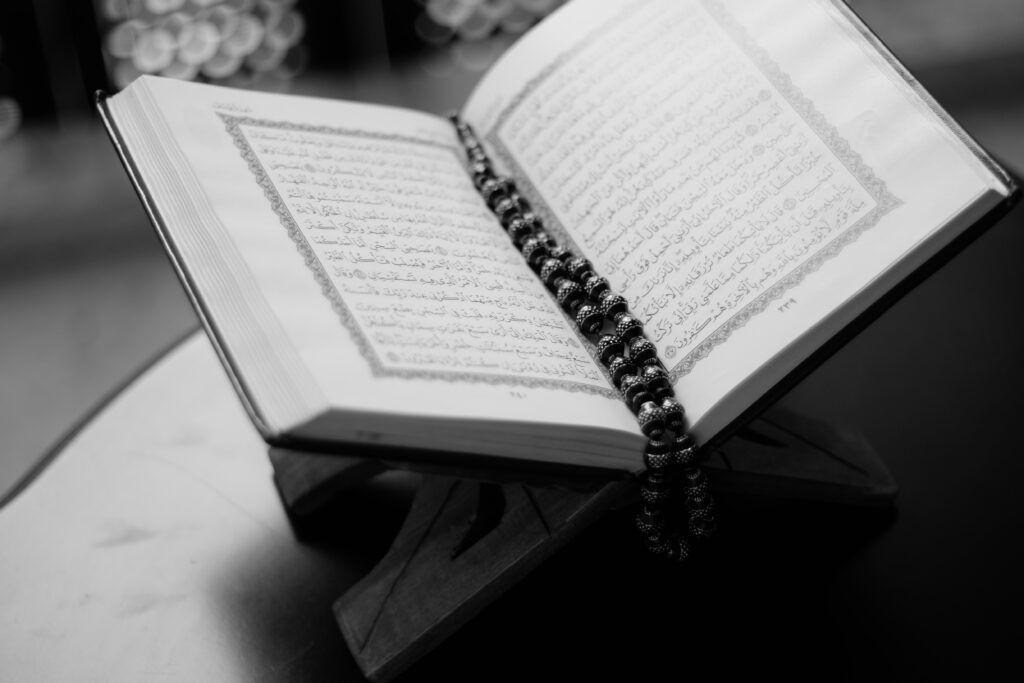

Hajra Rehman explains the core principles of Islam which have helped keep the pandemic under control in Muslim nations.

In the early days of the global catastrophe that is the Covid-19 pandemic, it soon became evident that precious human lives would be lost. It likewise seemed inevitable that Muslim-majority countries, a demographic of the global population which has seemed particularly prone to a wide range of disasters in recent decades, would be one of the regions where destruction would reach its horrifying peak.

A lot of these unspoken assumptions can be attributed to certain obvious facts about the Muslim world. Corruption, weak economies, religious fanaticism and wars have for decades crippled Muslim-majority nations with long-term negative effects. The last thing the Muslim world needed was a killer pandemic.

There was also the stereotypical suspicion that Islam is somehow incompatible with science and that the proclamations of the religious clergy and scholars, as well as Muslim traditions, such as Hajj and the five times a day call to prayer, would exacerbate the virus to the effect of devastating the populations of those nations.

However, what has transpired in recent months has perplexed many of Islam’s critics and bolstered and strengthened the hope of hundreds of millions of Muslims across the world.

Countries like Pakistan, Turkey and Iran have all managed to largely contain the virus, and much of this can be attributed to the spirit of fraternity imbedded within the DNA of Islam.

The charitable spirit and magnanimity of the people have eased the effects of the dilemma which every nation has faced: restricting economic activity while striving to prevent living standards from plummeting.

One great example is Pakistan. Yes, that same nation which has been riddled with a multitude of problems since its creation as a state in 1947. Crippled by corruption and homegrown terrorism and with one of the world’s worst performing economies, Covid-19 would just be one more nightmare to add to the country’s lengthy list of woes.

Indeed, its Prime Minister Imran Khan predicted that either people would die from the virus if they were allowed out or die from hunger if lockdown were fully imposed. Pakistan doesn’t have the resources or finances to provide aid packages and support schemes to its businesses and citizens. However, this nation has become a shining example for neighbouring countries in its endeavours to flatten the Covid curve.

The partial answer to this lies in zakat. Zakat is one of the five mandatory pillars of Islam and in Arabic means “that which purifies”, and is one of the most important religious duties for Muslims. It states that every individual, if they pass a certain financial threshold, must give 2.5 per cent of their total net worth to those less fortunate.

This concept is rooted within the ideology in Islam which states that life is fleeting and ultimately belongs to the Creator – thus no one truly owns anything, and those who are born less fortunate have the right to greater support.

This law of generosity is enshrined in Pakistan’s constitution, though Pakistan is one of only six countries, out of a total of 47 Muslim-majority states, where Zakat is mandated. According to the Stanford Social Innovation Review, Pakistan contributes more than one per cent of its GDP to charity, which puts it in the same league as countries as the United Kingdom (1.3 per cent) and Canada (1.2 per cent).

Moreover, a national study found that 98 per cent of Pakistanis give to charity. Given that approximately 24% of Pakistanis live below the poverty line, this is a figure that far exceeds the number of people who are actually obligated to offer zakat.

At the same time social initiatives have flourished. There has been the growth of volunteer organisations such as the Robin Hood Army which has been tasked with distributing excess food from restaurants and food factories. Groups like the Edhi Foundation have set up a system of centralised helplines and WhatsApp numbers which people can message to inform them of families in need of food.

A similar approach to Zakat has been taken by Turkey which has also been ranked one of the highest countries in the world for charitable organisations and humanitarian aid. And how has it achieved this? By mobilising its upper and middle classes to use their privilege to combat the virus.

The Turkish Red Crescent has called upon hundreds of volunteers who have managed to deliver food supplies to some four million of their fellow citizens. In addition, the charity has been active in poverty-stricken countries such as Somalia, Senegal, Palestine and Afghanistan. Similarly, the TDV charity has reached out to more than 20 million people in Turkey with a focus on the elderly, women and children as priority groups. Turkey has provided food and medical to aid a total of 57 countries in their own battles against the Covid-19 pandemic.

One of the initial epicentre nations of Covid-19 was Iran. However, through many months of sustained effort, the virus has become relatively contained within that country. Through a local charity called the People’s Relief Headquarters, approximately 15,000 of the most vulnerable families in one of the worst affected regions, Qom, have received financial support around 118 U.S. dollars to each family, a huge sum in Iranian currency.

Across Iran more than $40 million have been provided by the national association of health donors and $5 million have been donated by charities affiliated to the country’s hospitals. Nearly $9.7 million have been provided by non-governmental organizations and charities, and nearly $6 million by public volunteer groups.

The efforts of Muslim countries to contain the virus could simply not have been achieved without the cooperation of the religious clergy and scholars, often the most visible and powerful presence within the respective nations.

For example, in Iran the chief Ayatollah paved the way by practising isolation at home and temporarily ceased his teaching and subsequently other clergymen followed suit. Clerics also accepted the closure of shrines and mosques, as well as the sacred Friday prayers.

All these actions reflected true Islamic values: protecting your life and saving others is the most important religious duty of all and thus a sufficient reason to justify the suspension of public worship.

In the battle against Covid-19 there are no winners. However, in these times of adversity, societies of the Islamic world have succeeded in using their religious intuition and traditions to protect life, understanding that brotherhood, charity and the sanctity of human lives are all core principles of Islam, and indeed any religion.

Only through a collective effort can any community or nation face this moment of danger and come together as a formidable human force to defeat an invisible and deadly enemy. As Abdul Sattar Edhi, one of the world’s greatest ever humanitarians, stated,

“My religion is humanitarianism, which is the basis of every religion in the world.”

“Do you see this woman?” – Perhaps that should become the standard answer to anyone who takes it upon themselves to monitor women’s clothing choices according to their own idea of what modesty is supposed to look like at face (or bodily) value.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

One Comment

Frank Ulcickas

Enjoyable and interesting article. But I wondered how one can make a judgment on the success of dealing with the pandemic. Are not the majority of these Muslim- led governments repressive ? I wonder how accurate are the results reported.

Supporting the positive effects of personal charity is admirable and noble. I think possible in countries like USA with low tax rates. But far more difficult in leftist socialistic countries which confiscate so much of its citizens income.

Hoping for more articles from the author.