The Eyes of Annie Swynnerton

Adam Brocklehurst learns life lessons from a forgotten English artist whose work challenged attitudes to women in her time.

The Symbolist painter Annie Louisa Swynnerton is barely known outside her native Manchester. In her lifetime she was a highly regarded and internationally-recognised artist, who exhibited her work globally. Such artistic luminaries as Auguste Rodin and John Singer Sargent praised her ability. She was also the first elected female member of the august English Royal Academy of Arts since its foundation in 1768.

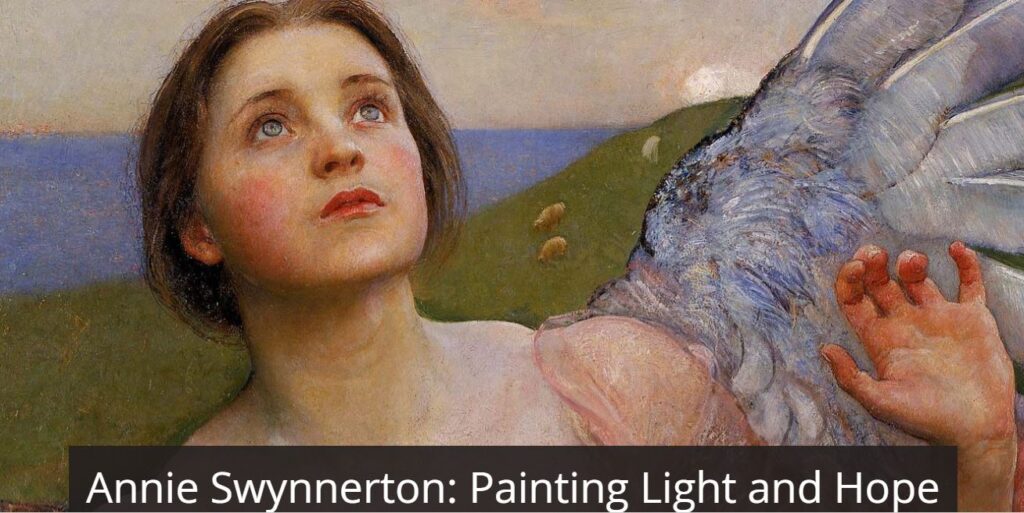

A suffragette and proto-feminist, she founded several artistic schools for women and, like the best activists, wanted to carry other women upwards on the crest of her own success. Surprisingly, the first major exhibition of her work since her death in 1923, Painting Life and Hope, was held just before the Coronavirus pandemic in Manchester Art Gallery in 2019. I attended and was struck by the power and originality of her work. The century-long neglect of her talent, therefore, made me pause for thought.

Annie Swynnerton was born in 1844 into a comfortable middle-class family in Manchester, a rainy city in England’s North-West, her father Francis being an attorney-at-law in the town. As a child she lived at 44 Dover Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock. The road faces directly onto the world-renowned University of Manchester, now famous for its connections to atomic theory, Alan Turing and graphene. Just a stone’s throw away from the Swynnerton home lived a young Friedrich Engels, author of the profoundly influential The Condition of the Working Class in Britain (he would later co-author the Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx).

Engels knew Dover Street well, he was a member of the German expatriate Albert Club, situated there. Also living nearby were the mercantile Goulden’s, whose daughter Emmeline, a friend of Annie’s, is perhaps better known to the world by her married name, Pankhurst. She would secure the vote for millions of women in Britain as part of the Suffragette Movement. Both socialism and suffrage would have a major influence on the artist’s work.

Annie trained at the Manchester School of Art, the same school that would later produce another great idiosyncratic English socio-political artist, L S Lowry.

She spent much of her life working in Rome, before returning to England and settling in London.

Her early style, while broadly conventional, utilised the impasto technique, a heavy hand with the paint and the brush, giving the canvas an almost sculptural and dramatic quality. She would remain faithful to this method throughout her career. Though in her youth her colour palette leaned towards the dark, in later life her work was known for its sun-drenched and luminous quality, perhaps recalling her appreciation of Italian light.

The great proponent of the Symbolist aesthetic, the school that Swynnerton aligned herself to, was George Frederick Watts, once an international celebrity whose paintings were much sought after, and who is now, like Swynnerton, rather relegated to obscurity. His personal maxim was ‘I paint ideas, not things’. He believed he painted absolute truths, metaphysical revelations, often with such profound titles as The Dweller in the Innermost (1885) and Time, Death and Judgement (1897). Swynnerton painted ideas too, her own philosophical perspective permeates her work, except her ideas were grounded in this world, in reality, in the lives of women.

Traditionally art depicting women was painted by men, to please the male gaze.

Men, after all, were the arbiters of taste, they controlled the exhibitions and the galleries, it was men who commissioned and collected, it was male money that paid for art. So, in most galleries, we are faced with canvas after canvas of nude or semi-clothed women, such as William Etty’s The Sirens and Ulysses (1837).

(c) Manchester Art Gallery

This hangs near Swynnerton’s portraits in Manchester Art Gallery, and it might be more appropriately named ‘three naked chicks on a rock’. I use this disrespectful term deliberately because, aside from the flimsiest attempt at providing a wider narrative, that’s what the painting represents. It is, to my eye at least, a canvas that objectifies women simply as bodies and is mainly artistic titillation. The danger that should be present in Etty’s rendition of what could have been a disturbing and thought-provoking piece, perhaps in the same vein as Géricault’s brilliant The Raft of the Medusa (1819), is reduced to the gratuitous; the sirens’ fatal allure is entirely passive.

(c) Wikipedia, Creative Commons

Swynnerton’s women, on the other hand, return the viewer’s gaze confidently, quizzically, sometimes with a touch of hostility.

She was once herself described by a critic as ‘embarrassingly outspoken’. And while they are beautiful women, it’s not beauty in the conventional sense that strikes us as we view the painting, the subjects’ beauty is present in the very reality of the women.

Her late work The Southing of the Sun represents an Italian peasant woman, approaching the viewer with her arms outstretched, and that’s exactly what you get. She is wiry, her face is heavily lined, presumably from years of hard labour outside in the fields under the scorching Mediterranean sun. Her untidy hair has been sun-bleached a dirty yellow.

(c) Manchester Art Gallery

There is absolutely no idealisation apparent, yet you get the sense that this woman has strength, that she is tough, that she has earned the right not to be trifled with, and that she may not be a particularly nice personality either!

Radically, Swynnerton has allowed the sitter to be herself, regardless of the usual social or artistic expectations of how older women should be represented in art.

And the disquietingly weird opalescent eyes, that appear again and again in her work, suggest something powerful, something otherworldly, almost as though Swynnerton has the key to a parallel world, hidden behind that sunburnt face, and those intense blue skies.

Annie was equally famous for her portraits of the offspring of these women, and the children she paints, as you might expect, are not apple cheeked and sweet but are instead real children, untidy and mischievous. There is an elfishness to their faces, not in a cutesy way, but with a peculiar knowingness, a sharpness of vision, their lips are too red, the colouring almost too bright, you want to cover your eyes … It’s not unlike looking directly into the sky on a hot July afternoon.

And there is something of the changeling in her handling of them, those infants that were rumoured to be the dark replacements of stolen babies, left by the fairies, that look almost exactly like the originals. Almost, but not quite.

These children are indeed different, it will be this generation who, as adults, will beckon in the world we appreciate today, who will begin to benefit from the equalities fought for so valiantly by their mothers: the right to vote, maternity leave, equality of pay, the right to ownership and the right to escape abusive marriages, things only dreamt about by generations of women before.

I think the artist knew what she was doing. I think her paintings of women were supposed to make men uncomfortable, they were supposed to suggest that strength lies beneath, if only they cared to glimpse behind the feminine mask. And their directness is a warning to men, at a time when the suffragettes were engaged in terrorism, burning and bombing property, taking on the state, sacrificing their own lives, and demanding equality by force.

Her paintings were her mandate, her protest, her contribution to the battle for full enfranchisement.

Swynnerton was painting unabashedly real women, women that other women could relate to at a time when the male prerogative still ruled supreme. And she returned the female image to its originator, women themselves.

Whilst it’s true that, structurally, things have improved greatly for women and that equality is engrained in law, we still have a long way to go. Protests have rocked Britain in the last few months following the appalling kidnapping and murder of Sarah Everard, snatched as she walked home on a busy street in London.

Annie Swynnerton’s work reminds us that humanity is very much a work in progress; we have moved on in leaps and bounds over the last century, yet perhaps we have become complacent. But complacency wasn’t a feature of Annie Swynnerton’s life and her art reminds us that it shouldn’t be the defining characteristic of ours either.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Related articles: