A masterpiece or mishap? A church which reignites the debate over 60s architecture

Adam Brocklehurst visits a Manchester church and discovers a powerful monument to God and modernity.

The church of St Augustine of Canterbury, a dark brown brick cuboid building, sits almost unnoticed behind a screen of trees outside a small park in the inner-city district of Manchester. Its monotony is broken only by an asymmetrically placed portico of four plain brick pillars. Outwardly it is not an ostentatious church, and it blends in cohesively with the surrounding buildings of Manchester Metropolitan University.

The church is the latest of a series of Catholic churches within this neighbourhood that have borne the name of the man responsible for converting England in 597 to Christianity (Augustine is known as the Apostle to the English). The first dated back to the time of the emancipation of Catholics in Britain in the late 18th century, whereas the previous building that stood nearby was destroyed during the blitz.

This incarnation was designed by Desmond Williams, an architect known for his innovative urban churches, and was constructed between 1967 and 1968 in the post-war late Modernist period. His aesthetic favoured functionalism over unnecessary decoration, based on elegant line and the use of honest building materials, exposing construction and natural light. The style has its roots in Art Deco, the work of Le Corbusier and Bauhaus, and is a half-sibling, or perhaps a cousin of a slightly better temperament, to the polarising and powerful Brutalist Movement.

This kinship to brutalism might answer for why modernism in church architecture gets the traditionalists, both religious and secular, so upset.

I’ve heard similar modern churches described as satanic or blasphemous by those frightened by the starkness and unfamiliarity, and even some who would argue for building preservation in any other case, suggest that the world would be better off without such structures as this.

Perhaps it’s because the great plains of exposed concrete or brick offer nothing to hide behind that offends the critics so much. There is no great weight of ecclesiastical or artistic baggage attached to the architecture to emolliate the human need to cling to the recognisable.

In truth St Augustine’s isn’t really all that radical: its floor plan still carries all the traditional elements: a narthex, a campanile, chapels, stained glass and a sanctuary. What it does away with are all the usual tropes we associate with church buildings in Britain. There are none of the neo’s in evidence, no neo-Gothic, no neo-Georgian, or neo-Italianate. It is not only stylistically but personality-wise a building of its time, with the surety of the self which characterised the 1960s idea of the individual and individualism.

The work at St Augustine’s was a three-way collaboration between architect Desmond Williams, Bob Brumby, a Yorkshire-born ceramic artist responsible for the sculpture inside and outside the church and most of the fittings, and the renowned avant-garde French glass artist Pierre Fourmaintraux.

It was Fourmaintraux who introduced the dalle de verre technique of glass manufacture to Britain whilst working at the Whitefriars glass factory in London. His abstract glass, set in slabs in tall slashes of windows, drenches the interior with colour. One window is gorgeously red hued, made even more so by the radical use of heavily sculptural black glazing bars.

To me the glass represents a panorama of Golgotha, Christ’s place of torture and death, repeated in cycle, a sea of repeated crosses, bent and blackened, stark against a tormented sky.

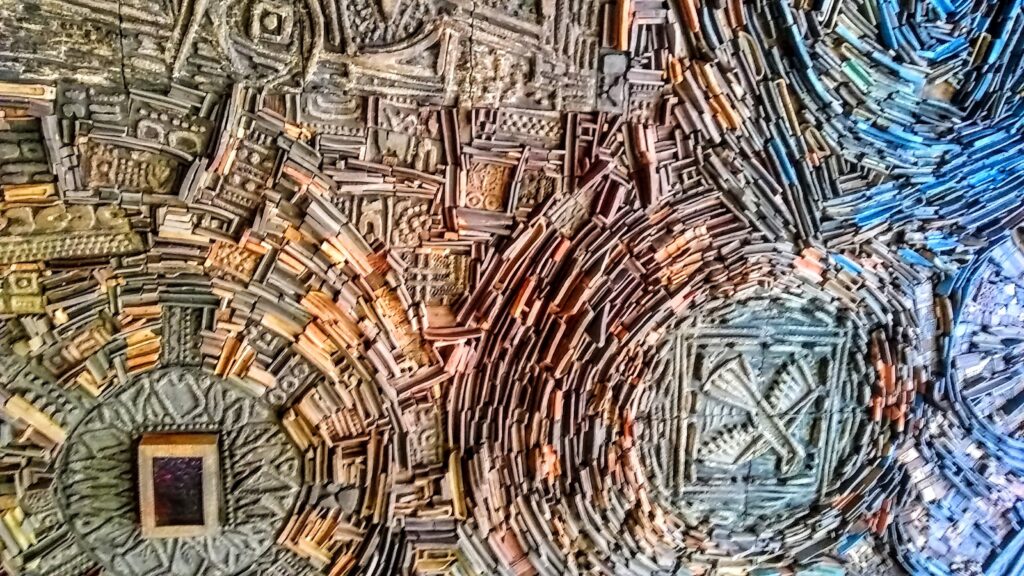

Brumby’s magnificent reredos – Christ in Glory – dominates the entire interior. It is, in my opinion, one of the greatest pieces of 20th century sculptural religious art anywhere. It is simply world class. If it were removed from its context (God forbid) and placed in a prestigious gallery of modern art, it would be as coo-ed over and ardently admired as any Henry Moore or Barbara Hepworth sculpture ever was by the world’s artistic mavens and aficionados.

Architectural historian Richard Brooke mentions how contention arose between the architect and Brumby over the fear the reredos would overpower the rest of the building. It is an unquestionably powerful work, there is little distance between Christ and the congregation. The architect’s remit was to make the sanctuary as accessible as possible, and he succeeds brilliantly; with its womb-like cradling, or solemnity of the sacred grotto, it is a great expression of both power and intimacy.

And the naturalism of Brumby’s handling of the thousands of individual ceramic components is quite staggering. Each separated piece is as finely worked as the next; each piece, seemingly unique, brings something new to the table, with a kind of collective unity as they swirl around and embrace the symbols of the Eucharist.

The reredos recalls the work of the great Russian-American sculptor Louise Nevelson or the Scottish-Italian maestro Eduardo Paolozzi. Though I suggest that here Brumby outshines the others as he dares to work his abstracts infinitely more tightly, more competently than either. His altarpiece appears like a shattered megalith, an open stratum of slate, exposed by a landfall and washed clean by rain.

What he is perhaps saying, considering that this church replaces one bombed in a time of war, is that the trauma of a break can be shifted into something elemental, something infinitely more beautiful than what existed before.

Christ, sitting enthroned with arms outstretched in welcome is a truly awesome figure. Here is Christ in Glory, Christ in Majesty, and there is no denying his strength. Brumby has wrought him elongated, byzantine and full of pathos. This is a Christ who wears his tribulations on his face; there is no sense of the heroic … he is a veteran, a survivor, Everyman who has seen his battles through to the end, and who stoically bears the weight of our sins. He is a triumph of realism, an antidote to the mawkish indifference of repetitive Victorian and Edwardian figurative, classically derived, representations of the Messiah.

Thats not to say this representation is to everyone’s taste. One friend sees the building as a box and struggles with what he describes as the intense owl-like eyes of the sculpture and the rectangular formlessness of the body. I’m completely sympathetic, better a strong reaction in the negative than a dismissive ‘meh!’ Art and architecture should be a source of debate, and debate on religious art especially has the power to draw people closer to what these images represent, to the deeper meanings inherent in them. And we both agree that the building’s atmosphere invites to prayer.

In a more worldly sense Brumby is recalling the stark power of Alberto Giacometti and, through him, the lineage back to Cubism and Surrealism and further back still to Auguste Rodin and his precedents. Unlike Giacometti, whose work shrinks from the observer, becoming smaller and smaller and more indistinct and introspective, Christ in Glory is confident, he challenges us, questioning our preconceptions of what it means to be Christian, what it is to be church, he invites us to re-evaluate ourselves in relation to him.

St Augustine’s was built in the era of the battle for civil rights and female liberation, of the struggle to remove the shackles of imperialism, under the cloud of the Cold War Soviet Union, and the need to demolish walls both literal and figurative.

Christ in Glory is an activist, a reformer, a turner of tables, an embodied indictment against what many believed to be increasingly moribund hierarchies within the Catholic Church, opaque liturgical practices and an alienation between the people and the Word.

Christ grows out of the soil of Vatican II, the great reforming Church council of the 1960s, and looks confidently towards the millennium. He re-establishes a sense of communion through active participation between the people, the priest, and the Body of Christ. In a very literal sense obstacles which once stood between him and us have been broken down.

Today there is again the sense that Christianity is becoming political, as world religious leaders speak out against political wrongs and attempt to act as peace brokers. War is reality in Europe once more, and the great world powers are shifting dangerously. The threat of global war, once unthinkable, seems horribly plausible.

There are growing rumbles of discontent between political factions on the left and the right across the world (was there ever not?). The question is, will artists and architects rise to the occasion and produce buildings and art which document these turbulent times and so bring faith into the centre of the debate with the brilliance and honesty of Williams, Brumby and Fourmaintraux.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Adam Brocklehurst

Adam Brocklehurst is a writer for Adamah Media. He graduated from Luther King House in association with the University of Manchester with a Masters in Contextual Theology, after undertaking his Bachelor’s degree in History Theology and Ethics at Bishop Grosseteste University Lincoln, and did much better than he or anyone else expected.

3 Comments

Bernard Leach

I thought that Adam Brocklehurst’s article on St Augustine’s church was excellent. I know the church well. I went past it often as I worked at MMU in several buildings close to St Augustines, including the Cavendish Building and St Augustine’s building (the old primary school). Furthermore, my mother (neé Celia Gerrity), a devout Catholic, in her later years viewed St Augustine’s as her parish church and I would go there for Christmas fairs and the like. When my father died the requiem mass for him was held there.

So it pains me to say it but I had little regard for the Church as it didn’t look like a church should. Adam’s article has opened my eyes to the treasures that lie within the church, and did that rare thing, it changed my whole view of the church

I am a member of the Royal Exchange Elders. We have held almost daily zoom callls ever since the pandemic began over 2 years ago. I host one of these each week and last Sunday did a presentation on St Augustines based around Adam’s article and my reaction to it. It is available on youtube at https://youtu.be/NLW2rqg22aU

Perhaps you could let Adam Brocklehurst know about this as it was both a tribute to St Augustines and to Adam’s article. I also got several people interested in going round and having a tour round the Church. Is there any chance that Adam might be willing to show us round some time?

BTW Adamah is an excellent online magazine and I am glad that I found it

many thanks

Bernard Leach

Tascha von Uexkull

Many thanks for your comments Bernard, it’s lovely to hear how eye-opening you found this article & thank you for sharing the video too! I will pass this all onto Adam and ask him about the potential tour too.

Thank you, we really appreciate your readership and hope you enjoy many more Adam(ah) articles to come!

Best wishes,

Tascha (managing editor of Adamah)

Robert Brumby

I stumbled upon this article while browsing for something other, and was astonished, and moved by the remarks made therein.

I wish to thank Adam Brocklehurst for his thoughtful, and generous appreciation of a work I was commissioned to produce in the mid-sixties. ( and still alive to read it)

I have done other stuff over the years, and maybe, someday, someone will come along, and join all the dots together, to complete the story. However, I doubt if would be alive to read that.

Thanks again Adam.

Best regards

Bob