When the storm clouds gather inside

Zoë Dukoff-Gordon reads a book about weather where the storms are more personal than meteorological.

I often find myself wondering: what is more worrying, the global threat of climate change or the growing fragmentation within our society? Should I be more concerned about the unpredictability of the elements or the erratic populism of political leaders?

And when so many people around me care more about acquiring the latest consumable than about facing up to such major threats, it seems to me that our society has its head firmly and contentedly buried in the sand.

It was therefore heartening to discover that I was not the only one with these concerns. I have found solace in the author Jenny Offill who has explored exactly these themes in her most recent novel, Weather, published earlier this year.

Weather follows librarian Lizzie Benson, who got “this job even though I don’t have the proper degree for it” (though she actually dropped out of university to care for her addict brother, Henry). She lives with her husband Ben and son Eli during a time when the turbulent weather is both physical and political. The plot consists mainly of accumulative thoughts, told through astute, satirical and acutely dry reflections, rather than a conventional story with a beginning, middle, and end.

Personal accounts of Lizzie’s own complex family life are interwoven with wider issues of the world she inhabits. This is partly told through the observations she makes as a newly appointed shrink-cum-agony-aunt, after she is enrolled to respond to listener’s queries for the podcast Hell and High Water run by Sylvia, her former lecturer and now an acclaimed author.

The novel explores complex yet pertinent themes in a subtle way: class divisions, demagoguery, racism and xenophobia. There are more explicit hints at the incoming Trump era and global political unrest, but the inevitability of the climate crisis takes on a persistent precedence throughout the narrative. Lizzie talks of the rich planning to “invest in floating cities, the kind that can be anchored in international waters and run by unmeddlesome governments […] They have nagging questions. What will be the safest place?”

The narrative, however, is not didactic. In fact, the narrator adopts a much more observational role. And the way the narrative is structured is extremely fragmented, a reflection perhaps of the fragmentation in Lizzie’s own life and the society around her. Whilst this serves as a narrative device for the narrator’s thoughts and the complexities of the modern age, it also gives the reader some freedom of movement within such overwhelming discussions.

It feels as if the novel is placed back into our hands; the political action becomes our choice.

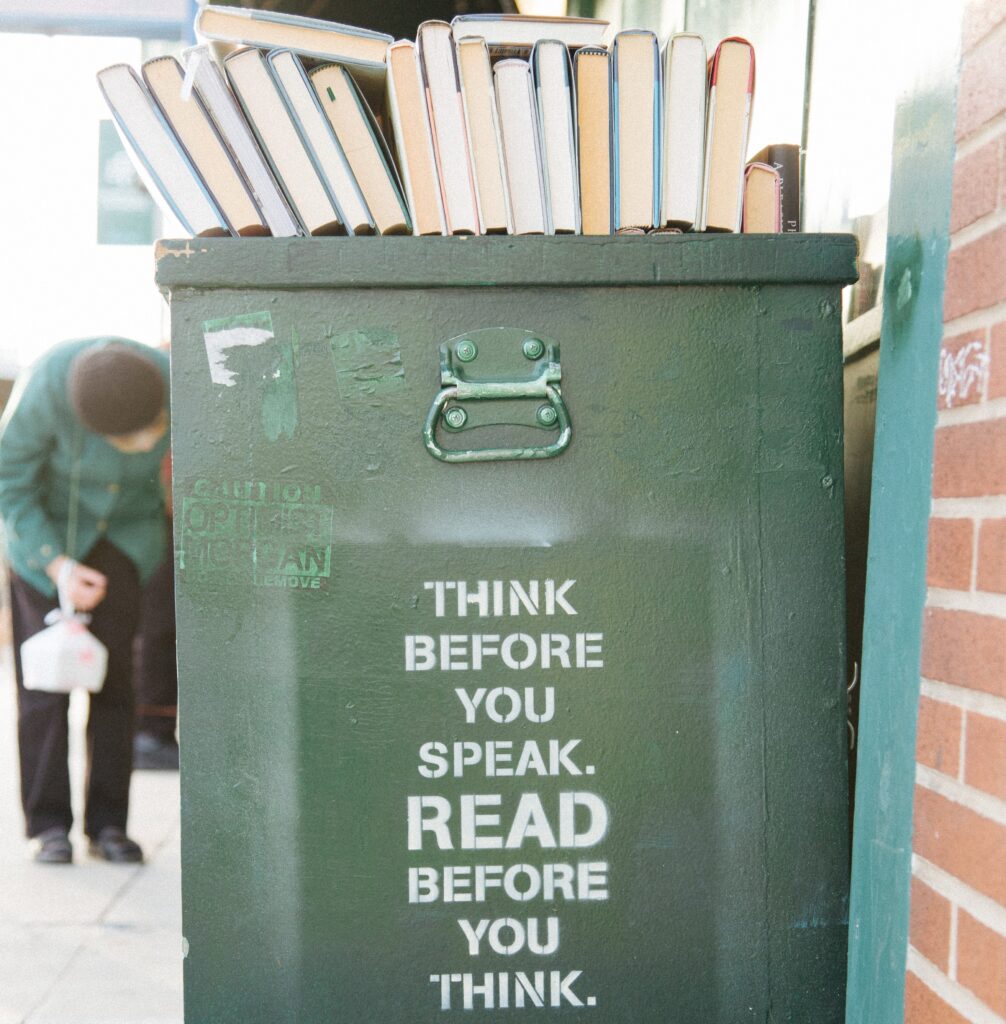

Why is such an implicit form of political examination more potent than an explicit commentary? Perhaps because it highlights our own lack of active engagement, making us more aware of the irritation we feel as readers who cannot intervene, who cannot enter the pages of the novel and shake its characters into action. Therefore, the only control we are left with is over ourselves.

While the self-reflective nature of the novel also troubled me as a reader, it did not put me off, and hopefully won’t put others off either. The self-awareness Offill writes with was the wakeup call I needed, that we all need.

I found reading the submissive responses of her characters to the climate crisis somewhat unsettling. Their anxiety – very real but very superficial – spurs them to react as consumers rather than as political citizens. The aforementioned plan to “invest in floating cities”, for example, is an acute and disturbing insight into our tendency to be consumers rather than active and engaged individuals within a society. To prefer purchasing over political action.

Offill offers her characters a Fight, Flight or Freeze response; and only the latter two play out. There is often a psychological interplay between denial and suppression when difficult thoughts and events arise – something we might all have experienced – and Offill allows these responses to dance with each other through her characters.

Offill shows us how many people react when faced with testing challenges: on the one hand there are the consumer workers drifting in political unrest, and on the other an objective narrator who is detached from the external events around her. She is an observer, much like the submissive position many of us tend to take. The passivity is frustrating; but mostly it is exceptionally frightening.

If “God is dead”, to use Nietzsche’s phrase, we have little left to fill our existential void, except to be ever more workers and consumers. With the disappearance of religious value systems, we no longer have the clear principles which once inspired political action. And so now, as we scroll through the news on our smartphones, our responses are reduced to likes, shares, and comments.

The novel made me aware of my own passive political engagement, particularly within the climate crisis. I often share petitions, facts, like or ‘react’ to posts about sea turtles and ocean plastic. Yet, once my smartphone (made in China, by labourers with dire working conditions, and designed to last only a few years before it ends up in landfill and I buy another one; perpetuating the cycle – ironic, I know) is put down for the day, my activism subsides.

And then, on a personal level – through the protagonist, Lizzie – I was reminded of some important yet often neglected issues in my own life. How easily one can be distracted by the isolating monotony of work and consumerism. The narrator does not have anyone with whom to talk her issues through. She very much observes other people’s emotions, but at a detached level. She feels like a vehicle for other people’s concerns.

The characters Lizzie interacts with feel equally disconnected. She replies to emails for the podcast Hell and High Water from people she does not know. The only close relationships she has are with men. Men she cannot personally identify with; whom she constantly tries to fix, and consistently cannot. These relationships make the novel feel very impersonal, very isolating, and incredibly lonely.

And once again this impersonal quality forces a personal response from us. We are not guided by our protagonist’s emotions; the reader is therefore left only with their own emotional reaction. When Lizzie is caring for her brother, the induced reaction is how you would feel if it were your brother.

When she is tempted by – and falls into – infidelity, leaving her feeling only more lonely, the reader is encouraged to question: what would I do in this situation? You are drawn to reflect on your own romantic relationships, your own happiness, your own conflicting and difficult emotions, on the people you invest your time in; and whether your investment receives any returns. The novel creates a well needed space for self-examination within its reader and, in turn, leaves us with the autonomy to make our own life decisions.

Weather brings together many feelings of shared anxiety, collective loneliness and cultural uncertainty. But Offill does not offer a solution. There is one source of hope, however, dramatised through the tender moments shared between Lizzie and her brother and her son. The novel reminds us to return to altruism. To reconnect with one another, and help those in need. To resolve differences, or at least accept them for what they are.

In conclusion, Weather explores the turbulent emotional and political weather of our modern age. The novel’s emotional intensity increases rapidly towards its end, almost as if the narrator suddenly realises the things she has never gotten around to doing, the mundane things which she has taken for granted, and so she rushes to attend to them all in the little time she has left.

And this stands as a reminder to us all to reflect on what is important in our own lives. Is it really that work deadline or that new all-absorbing material object? Or is it the people we often don’t make time for? It is a reminder too of the destructive rush which seems to be one of the worst ‘storms’ unleashed upon modern life, the race against the clock to which we all are prone to succumb.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!