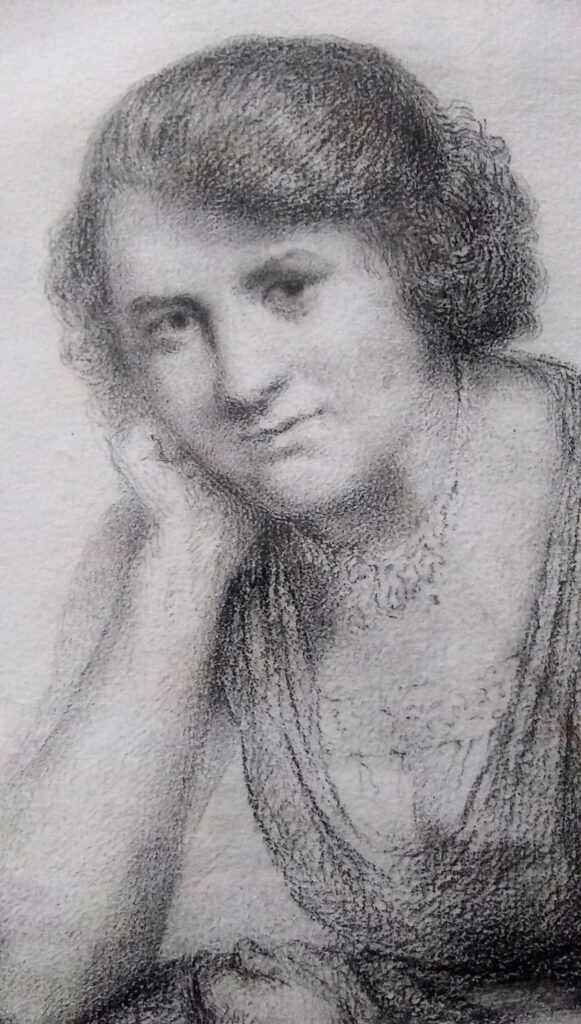

The likeness of Agnes Bamber

A chance discovery in a charity shop in Manchester, Northern England, leads Adam Brocklehurst to reflect on relationships across social divides.

Agnes Bamber would probably have passed out of this life unnoticed and been relegated to that great dusty attic of ordinary people long forgotten had I not stumbled across her portrait whilst rummaging through a box of old picture frames in a charity shop.

Her likeness is captured here by the Anglo-Dutch painter-priest Leo Arendzen using a graphite pencil and paper (now somewhat discoloured with age). But rather than showing a slim ingénue as one might expect from an artist of his background, he depicts a working-class woman who would have once been referred to in the local parlance, and not unkindly, as a strapping and homely lass.

Her thick hair is of a style fashionable in the late Edwardian period, and her expression is cheerful, with a touch of calm resignation. She has the kind of face which will inevitably age into a benevolent wizened apple, soft cheeks, small dark eyes, and a petite but firm mouth. Her ample bosom, trimmed with broderie anglaise, with a hint of décolleté, and her posture, one hand resting casually on her face as she sits informally, suggest a conversational intimacy between sitter and artist.

One suspects the priest-artist was fond of her, though without any suggestion of anything improper. It’s drawn with a light and confident hand, with a nod to the soft-focus technique used by French Impressionist Auguste Renoir in his drawings.

A dedication from artist to sitter survives on the back of the picture frame, written on sepia paper, giving us a sense of their affectionate working relationship.

This is the Likeness of Agnes Bamber

All ye, who look are asked to remember

Many a year she kept house for a priest

Making his life a long pleasant feast,

The years she was with him are almost twenty

Yet never she failed to serve him with plenty

Her virtues are more than I could ever unfold

She’s modest and humble and won’t have them told.

Agnes Bamber was born in 1895 to an English pork butcher and his Irish wife and spent much of her childhood living in a typically northern English small redbrick terrace on Regents Road Heavily, Stockport. In Agnes’s day this town was dominated by the great hat producing factories, its viaduct, and the ancient marketplace. It was a bustling place a century ago and remains so today.

The Bambers were an English Catholic family originating in the nearby sprawling city of Manchester, nine miles distant. They had been Catholics for a long time, perhaps from before the emancipation of Catholicism in the late 18th century. (The Catholic Church in England had effectively been outlawed for almost three centuries after the break with Rome in the first half of the 16th century.)

It is hard to be certain of this, though, for unlike local aristocratic recusant Catholic families such as the De Trafford’s and the Townley’s who were shielded to some extent by their great wealth, working-class Catholics were often more circumspect in documenting their faith due to the real threat of violent persecution. However, Catholicism had never ceased to be practised covertly in the region, and her ancestors appear in Manchester’s first legitimate Catholic church records after emancipation.

Agnes gained her position as cook-housekeeper with Father Leo around 1913 during his six years as priest in the nearby Calico producing town of Glossop, Greater Manchester (incidentally also the demesne of the greatest recusant family in England, the Dukes of Norfolk).

Her employment prior to her new situation had been as a confectioner, probably carried out between the heavy lifting and hard graft of salting and brining pork, and the preparation of brawn, pies, and sausages, and housework required of a butcher’s daughter. This experience, combined with the more specialised requirements of the preparation of jcakes, sweets, and dainties of the confectioner’s art, meant that Agnes acquired the prerequisite skills of a cook-housekeeper.

It was a respectable role for a young girl, with the prospect of job security and a high profile in the small community.

And the working relationship appears to have been a great success: she was still with Father Leo in 1939 during his long stint as Catholic Parish Priest at St Mary’s in Grantham, Lincolnshire, and probably stayed with him until his retirement 14 years later, in 1953.

Her charismatic employer had been born in Germany into an artistic Dutch family. His father was the distinguished Amsterdam-raised engraver Petrus Johannes Arendzen, and his mother, Epiphania, was born into the renowned family of Dutch sculptors, the Strackés. The family lived at 14 Quex Road, a large London townhouse in Kilburn, close by the church of The Sacred Heart, one of the final churches designed by the great Catholic architect E W Pugin.

As one might expect, their friends were intellectual and bohemian and included the fellow Dutch expatriate, and fashionable Victorian artist, Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Leo was one of five brothers, four of whom would enter the priesthood (his brother Fr John Arendzen is considered by many to be one of the most important Catholic theologians and evangelists of the first half of the 20th century).

His early life was normal enough but there was a definite unconventional streak in the young man. Leo trained at the Slade School of Art during one of its most exciting periods; fellow alumni included social realist Augustus John, Impressionist artist Ethel Carrick and late Pre-Raphaelite Evelyn de Morgan, and the young Leo practised as a portrait painter, before a late vocation to the priesthood.

According to his distant relation, Peter Stone, during his training to be a priest, amongst other misdemeanours, he was expelled from one seminary for keeping chickens on the roof. And he was later chided by no lesser person than the Pope for having long hair!

In my experience, living with an eccentric or free spirit can at times be a struggle and I imagine that on occasion Agnes found herself with her hands full.

His vocation didn’t stop his artistic career. He was known in Grantham, a market town in Lincolnshire, as the ‘painting priest’, and his portraits of prominent churchmen hang in various religious institutions to this day (although his skills were not limited to painting – it was Arendzen who taught Latin to the young Margaret Roberts, better known by her married name, Thatcher!)

What is remarkable about Arendzen’s portrait of Agnes is the amount of autonomy he has allowed her. It’s usually the artist’s prerogative to pose a sitter, to choose their clothing, and the context they will be depicted in.

If it had been Leo’s contemporaries Walter Sickert or Annie Swynnerton – both deeply political artists – who had drawn Agnes, it’s probable they would have painted her in her aprons and cap, working in her kitchen, perhaps up to her elbows in flour as she kneads the day’s bread. They would have defined her by her class and employment, as a means of saying something else, perhaps something important about women’s suffrage or the nobility of hard work. She would have become an extension of their own desires, a tool to critique society or politics.

Arendzen hasn’t done this. Instead, he’s depicted her as she would like others to see her, in her best frock, her hair neatly put up. He’s treated her as he would any other sitter, and that says something about the egalitarian nature of his character.

He is saying to us she has a life outside of his world, she is more than just a cook and housekeeper, she is her own person.

History is ephemeral and working-class history even more so, unsurprisingly when academics have long tended to write history from above, leaving us with a skewed vision of the reality of the past.

The relationship between Agnes and Leo, offers a nuanced snapshot into the lives of two ordinary people brought together in normal circumstances, yet it still has something profound to say about the nature of relationships in general, about seeing past the anonymity of uniforms, giving people who exist on the periphery of our lives an equal voice to our own. This is especially important today in a world where online goods and food deliveries, in a massive but largely unregulated service industry, threaten to re-establish a kind of second-class citizenry of people who exist purely to satisfy our passion for consumption

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Adam Brocklehurst

Adam Brocklehurst is a writer for Adamah Media. He graduated from Luther King House in association with the University of Manchester with a Masters in Contextual Theology, after undertaking his Bachelor’s degree in History Theology and Ethics at Bishop Grosseteste University Lincoln, and did much better than he or anyone else expected.