Reading a building colonially

They’re pulling down statues, but what about houses? Adam Brocklehurst looks behind the bricks and mortar to discover challenging truths about the culture that crafted some of England’s most iconic buildings.

Britain is currently in love with Nigerian-British historian David Olusoga’s A House Through Time, a programme that unpacks the history of dwellings through their owners and residents. Suddenly the British public understands that a building is more than its constituent parts, that it is peopled with characters and narratives.

Homes are both the repository of the elite and of uncomfortable truths, the two often living cheek by jowl. What Olusoga has taught us, primarily, is that a house can be political.

One particularly good illustration of this can be found in the Northern English city of Manchester. Milverton Lodge is a large detached neo-Gothic villa built around 1850, that stands not far from the University of Manchester in one of the most ethnically diverse neighbourhoods in the world. Until quite recently the Rampant Lion pub, it is now a hotel, Middle Eastern restaurant and shisha bar, reflecting the changing demographic of the area. But for the first four or five decades of its life it was the gracious home of James Ingham, a member of 19th century Manchester’s ruling cottonocracy.

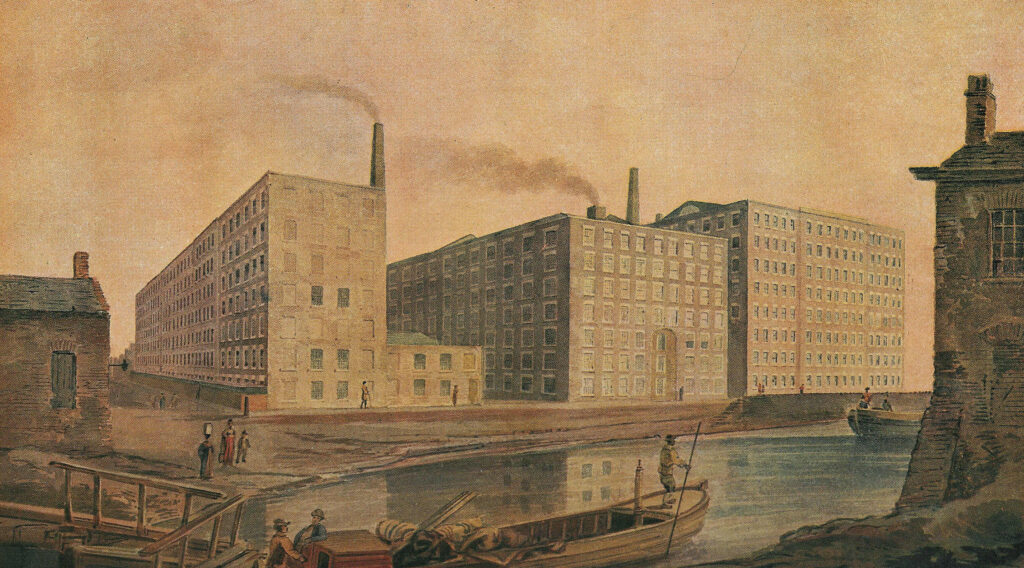

Manchester was then the centre of the greatest industrial enterprise ever undertaken in England. Vast mills took in tons of raw American cotton and churned out endless yards of fabric: the warehouses from which the goods were sold still define the cityscape.

Ingham was an engraver of calico, a plain-woven textile made from unbleached and often not fully processed cotton. The technique utilised engraved copper cylinders for printing calico through mass production. This method had been invented by John Potts in 1820, as an efficient means of printing patterns onto calico, producing hardwearing and decorative ‘Chintz’.

Chintz was a popular fabric for upholstery, hangings and clothing in Britain from at least the 17th century when the diarist Samuel Pepys records ordering Chintz goods for his wife Elizabeth. A bed made for the extravagant Prince Regent was moved to Kensington Palace for the use of the young Princess Victoria – later Queen Victoria – and re-upholstered in a pink sprigged chintz.

The word Calico is derived from the name of the Indian city Calicut or Kozhikode, a city in the state of Kerala. For centuries India was the sole producer of Calico, and a large-scale artisanal industry existed to meet demand.

Its cheap mass production in Britain was the final nail in the coffin for the Indian calico industry, already terminally impacted by the mechanised production of cotton in Manchester. This resulted in the destruction of a way of life for countless Indian weavers, inevitably leading to much material hardship.

While the likes of James Ingham in luxurious Milverton Lodge probably gave little thought to starving weavers and their families thousands of miles away, the reality of what was happening did not go totally unnoticed. The plight of the Indian cotton industry would lead Karl Marx in his 1857 The British Rule in India to declare, “It was the British intruder who broke up the Indian hand-loom and destroyed the spinning-wheel…”.

Marx was one of the few to recognise that whatever motivations the Imperial British might claim for their presence in India, the outcome was the destruction of competing markets.

By 1850 Lancashire was producing two million pieces of printed calico annually, and men like James Ingham were reaping the rewards.

Ingham was a gentleman and an entrepreneur. At one time these positions might not have been compatible: English gentlemen conventionally did not go out to work but instead drew an income from their land. By the middle of the 19th century, however, British society was becoming much more fluid, and a conspicuous show of wealth evidenced not only Ingham’s position as a gentleman but his success in business.

His home was an opportunity to gain the confidence of his investors, partners and buyers and Milverton Lodge was a conspicuous house in the most exclusive area of Manchester, Victoria Park. It would have left those around him in no doubt as to his ability to make money.

Gothic was regarded as an indigenous English style and Ingham wanted to be seen to be living in an English house when being English was a statement of great power.

The large windows are aesthetically perpendicular, hearkening back to the glorious Indian summer of English gothic following the Tudor period, where England liked to imagine its imperial roots began.

The perpendicular fenestration is married with elegant ogee tracery, an architectural flourish of the English decorated style of two centuries earlier. This was an imagined time of chivalry and courtly love, English fair-play and gentlemanly conduct, how we fooled ourselves into thinking we behaved in our newly subjugated Empire.

The roof is polychromatic and dramatic, making a feature of the utilitarian. Thirty years earlier the mansard would have been chastely hidden behind the cornice. Now the attic story has become central to the overall design; it is a conscious remove from the Georgian style of the recent past into a confident Victorian stride, which speaks of the primacy of the industrial revolution over the agrarian and the artisanal.

Such eclectic relationships were typical of the high Victorian taste, where an excess of architectural knowledge outpaced archaeological authenticity. There is no requirement of fidelity to one style because this is not an attempt to replicate an authentic medieval house. It is a verbose modern building that turns it back on the more patrician Tudorbethan and Italianate villas nearby, and calls out loudly, “I have arrived!” It is as much a testament to confidence at a time when Britain was supremely sure of itself, as it is to the ruthless success of the Industrial Revolution.

Manchester is often quite self-congratulatory about its industrial prowess. It has become almost totemic, something reified alongside football, Alan Turing and graphene as being positively emblematic. The city’s signature bee, signifying industry, is proudly displayed everywhere.

As a step towards reassessing our colonial past, David Olusoga warns us against valorising the likes of Cecil Rhodes or Clive of India, men who did great harm to countries they invaded or exploited during colonial times. He suggests men of their ilk should be taken down from their pedestals, literally in some cases, and their legacy reassessed in light of their actions. And he proposed this well before the Black Lives Matter demonstrations put this question high on the public agenda.

But why stop at people? Just as Ingham understood that a building and architectural style could conceptually mean much more than bricks and mortar, is putting our industrial past on a pedestal as something to be proud of any different from erecting marble statues to men who committed atrocities? And yet, we would all probably balk at the idea of crowds demolishing buildings, particularly beautiful ones. There are too many issues at stake and questions to ask before endorsing such an action. And is it possible that buildings can be redeemed?

In 2020 as we globally reassess our past in relation to racism, isn’t it perhaps desirable that Britain reassess the origins of its industry and therefore its wealth in relation to its colonial past?

Perhaps it’s time to examine the narratives of those overlooked Indian calico weavers and their families, who some might argue were simply collateral damage in the great capitalist machine and see what British industry meant from their perspective.

Then once we have an accurate portrait of who we were, and why we were, in relation to India and our colonial past, we can start climbing the steep hill towards atonement and reconciliation. Although for many Indians it might seem rather like apologising after one has already eaten, and enjoyed, the stolen apple pie.

British imperialism is now dead, alongside British industry. It is worth noting that as British industry failed in the decades after World War I, India purchased much of the redundant cotton producing equipment from Manchester mills and used it to re-establish its own long moribund industry.

India now has one of the largest workforces in the world, it has almost more billionaires than anywhere else and India Today predicts that the worth of the Indian textile industry will surpass $226 billion by 2023. India is now second only to China in the global production of textiles. While there are major issues regarding child labour, the impact on the environment and rates of pay, industry is raising the overall living conditions of those employed in it.

To paraphrase Gandhi, we can change ourselves, we are in control, we no longer need to continue spinning false narratives to shore up shaky national identity, we can be honest if we choose.

James Ingham, I suspect, would be more circumspect with the origins of his wealth nowadays. But he was a man of his time, and maintaining a psychological dissociation from reality was part of the imperial mindset. His home Milverton Lodge still stands, an important document in the library of industrial history, as well as a monument to a society that has yet to come to terms with the reality of its own past.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

4 Comments

Suzanne Tyldesley

It was owned by Arnold Burlin in the 50’s, 60’s, 70’s. It was a beautiful hotel with a great restaurant where the celebrities stayed. He was a friend of my fathers and started the Piles of Pennies in the pubs for charity. His sister was murdered by Christie. My father took me for a meal there when I was 16 and just got ny GCE results in1956. Always enjoyed going there.

Alan Reeves

Was this not the hotel owned by Arnold Berlin? He was the pile of pennies man.

news

That’s actually wise and thoughtful. Would it be ok to counter with a follow-up question?

Brenda Bouker

My grandparents were good friends with Arnold Berlin and my two aunties had their wedding receptions there approximately 1952.