Court watching in the United States

Kendra Mills explores a novel idea aimed at making America’s justice system fairer.

The United States imprisons an unprecedented number of its residents. According to World Prison Brief, the US leads the globe in the total number of people behind bars, though there are some questions as to whether other countries accurately report their data.

On the other hand, it is inarguable that the rate of incarceration in the United States far outstrips any other country, this despite recent reductions in the prison population.

The past decade has seen a groundswell of support for prison reform and abolitionist struggle, partially driven by the popularity of projects like Ava Duverney’s 13th, a documentary about the 13th Amendment and the prison-industrial complex. The 13th Amendment outlawed slavery in the US ‘except as a punishment for crime’. People incarcerated in both public and private detention facilities in the US work in fields and factories, often performing dangerous tasks like firefighting, for well under the minimum wage.

Reform advocacy and abolitionist struggle are often set in opposition to one another. Where the prison reform movement attempts to incrementally improve the conditions of mass incarceration, abolitionists seek to radically transform the justice system, ending mass incarceration and its inherent inequality. Despite their divergent priorities, many abolitionist leaders support specific reforms which improve the lives of justice-impacted people while retaining their commitments to abolition.

Of course, not all reforms are worthy of support. Scholars like Maya Schenwar and Victoria Law have observed that, while the prison population is waning in the US, detention has mutated into other systems of control, including punitive mental health interventions and supervised release programs. Electronic monitoring, an essential element of supervisory discipline, also involves a huge degree of financial exploitation, as the cost of electronic tagging is often borne by the wearer.

The pivot towards supervision enjoys a significant amount of bipartisan support, however, as traditional conservatives have begun to balk at the enormous state expenditure required by systems of mass incarceration. In truth, there is little clear impetus for conservative lawmakers to support monitoring technologies because, while their use enriches private companies, the state still bears the costs associated with policing, processing, and convicting offenders. Liberal lawmakers, on the other hand, profess to be motivated by factors beyond economic considerations, but they have also been quick to embrace mass incarceration when politically expedient.

For example, the current President and Vice President have both championed law and order policies throughout their careers. Joe Biden authored the infamous 1994 Crime Bill, which many cite as instrumental in the progression of contemporary mass incarceration, while Kamala Harris presided over the second most populous state prison system and fought against release orders from a federal judiciary when serving as Attorney General of California.

Despite the burgeoning criticism of incarceration, Biden’s first year in office ended with nationwide migrant detention surging by more than 50% when compared with the previous year. As noted by the Prison Policy Initiative, migrant detention is an important but often overlooked subcategory of mass incarceration. While the 2021 numbers are not radically out of step with pre-pandemic figures, they represent a disappointing return to policies of confinement. Police spending has also been augmented, despite calls for the redirection of resources.

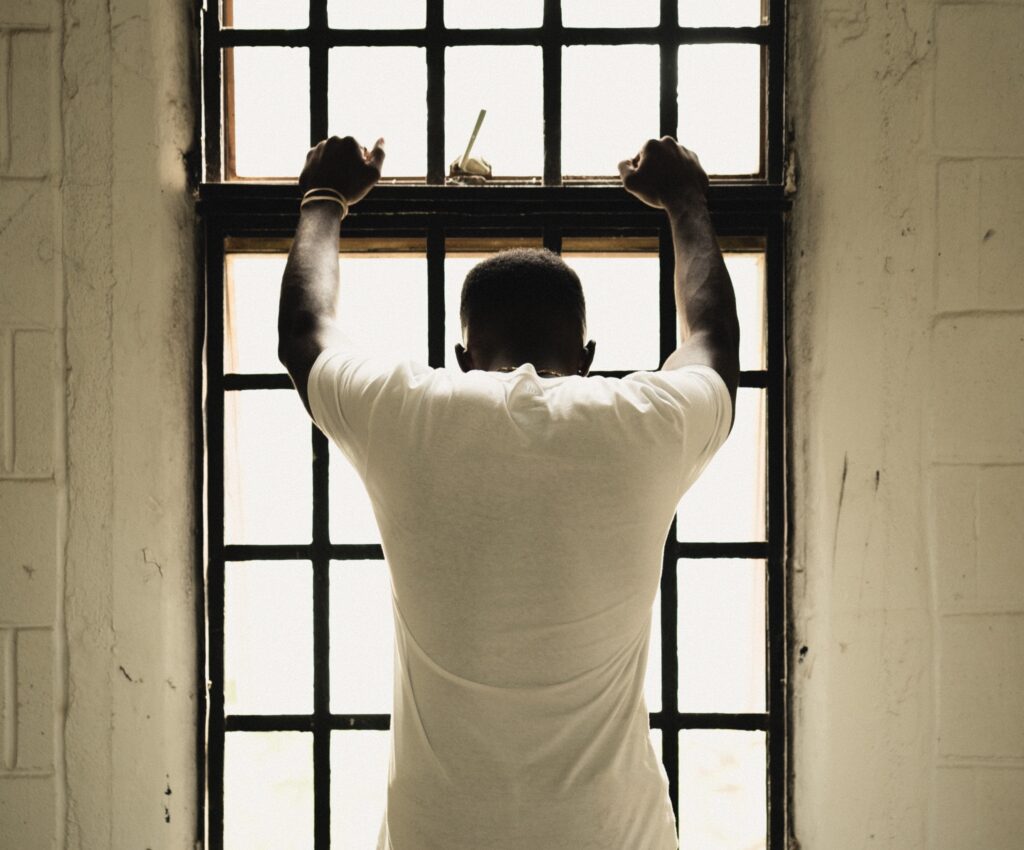

It cannot be emphasized enough that the phenomenon of mass incarceration unfairly burdens people who are already marginalized, in particular black men.

Moreover, there is a cyclical element to the processes of racism, financial hardship, and criminal justice intervention, wherein poverty and punishment reinforce one another.

In many ways, it can be easy to overlook the discriminatory qualities of the criminal justice system because its effects are so unequally distributed. Some US residents will likely come into contact with the criminal justice system continuously throughout their lifetime, while others will hardly experience it at all. But scholars have argued that in fact the treatment of impoverished black people in America can be thought of as a ‘canary in a coal mine’.

The automation of work and the intensifying concentration of wealth in the hands of a smaller and smaller number of people has made larger swathes of the population redundant to a society governed by market logic. Building off Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Angela’s Davis’s works, which theorized that prisons can be understood as a grim solution to the problem of surplus populations, Jackie Wang has argued that the tendency towards racialized confinement can be thought of as a forecast of one potential future.

According to this scenario, mass incarceration would expand to capture anyone superfluous to the market’s needs.

According to the New York Times, in 2011, Moody’s Analytics reported that the ‘top five percent of income earners account for about one-third of all spending’ in the United States, and suggested that the percentage will continue to increase. As such, it follows that people may become less relevant both as workers and as consumers, allowing them to be more easily swept up into the prison system.

But this dismal vision of the future is just one potential catalyst for solidarity with movements opposing mass incarceration, mass supervision, and general systems of punitive control. It is, after all, speculative, and we possess the capacity to believe in justice on other grounds than fear. In fact, Wang’s book is also a testament to her love for her incarcerated brother, another more personal catalyst for political mobilization and solidarity.

In a conversation about his recently released book, Understanding E-Carceration, James Kilgore and Ruth Wilson Gilmore spoke about the significance of an internationalist sensibility and the variety of grassroots accountability projects which rely on solidarity. Research, such as data gathering, can actually be a means of resistance against the prescriptive opacity of electronic monitoring companies (Kilgore pointed out that there is no centralized database which records how many people are being supervised by monitors in the US at any given time) as well as other disciplinary institutions, like the court system.

Bail reform movements have made use of court watchers as they advocate for the end of the bail system, which disproportionately punishes people who are impoverished and unable to pay. Court watchers are community members, unaffiliated with the court system, who appear in court rooms which haven’t been closed to the public, and observe the proceedings. According to US law, people must be presumed innocent until proven guilty. The requirement to pay for bail, even in the case of minor infractions, results in the confinement of scores of the legally innocent – namely those accused of minor crimes, not yet tried, but unable to pay to avoid being remanded in custody.

After significant struggle for bail reforms in Cook County, Illinois, the Coalition to End Money Bond prepared a team of volunteer court watchers to attend court in 2017 and answer the following question: “Have recent reforms led to a decrease in the issuing of money bond and electronic monitoring and [i]n cases where [a] money bond was issued, was the amount of the bond affordable to the accused person?”

In the context of the US legal system, where there is an excessive use of stacked charges – often, when quotas are set within a police precinct or a prosecutor’s office, defendants are subject to unnecessary charges in order to meet those quotas – careerist prosecutorial behavior, and simple overwork, it is impossible to overstate the importance of the work done by the court watchers who documented whether reforms had been applied and collected data for future advocacy efforts. In Cook County, they collected information on the demographics of the defendants, their charges, the types of bonds with which they were issued, and their respective affordability.

The court watchers found that the reforms had a real impact on the behavior of judges, but that in certain circumstances, other means of advocacy were necessary. For example, it became clear that defence lawyers should be reminded of their duty to inform the judge of their clients’ financial circumstances, to try to ensure that they were not incarcerated simply because they could not pay. As a result of the court watching initiative, the Coalition to End Money Bond was able to create a series of recommendations for future legislative advocacy and community outreach.

Court watching is not limited to bail reform. A number of organizations coordinate court watching in conjunction with sexual or domestic violence trials or to evaluate policing practices. The Sixth Amendment enshrines the right to a trial by jury and the right to representation. Also enshrined is the right to a public trial. Scholars have argued that court watching is an alternative method of ‘witnessing’, which Nick Gill and Jo Hynes argue is more active than merely ‘watching’. Despite the name, court watchers are not passively observing the proceedings, as the data they produce shapes activism and advocacy efforts.

In fact, court watching is judged by some to be an act of subversion.

The law is, ostensibly, meant to act as a mechanism of accountability for wrongdoing. Court watching can be thought of as an alternative way of holding power to account, as it engages in criticism of the very institution which is meant to administer justice.

What is perhaps most compelling about court watching is its universal accessibility. The US justice system, despite the entrenchment of values like impartiality, is, inherently, hierarchical. Tremendous amounts of information and expertise are unavailable to the public. Furthermore, there is a shared complicity between legislators, law enforcement, legal representatives, and judges (and to a degree other employees of the state such as social workers) which is inaccessible to the vast majority of people who might appear in court.

Court watching allows the community to correct this discrepancy and involves the public in advocacy for a better justice system. The Cook County court watching initiative offered free training and has distributed publicly the forms they used to meet their information gathering objectives. Other organizations have published toolkits to help collectives begin their own initiative.

Court watching embodies solidarity that requires few special qualifications and, in essence, offers an avenue by which to demand the justice promised – but unevenly delivered – by the justice system.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Kendra Mills

Kendra Mills is a graduate of the LSE human rights program, where she wrote her dissertation on the pivot to mass supervision in the United States. She has previously written about the tensions between privatization of resources and human rights, technologies and justice, and international drug policy.