Toppling the truth: a monumental matter

Donal Durrihy takes an alternative view to the prevailing mood on the removal of controversial statues.

“England is always remaking herself, her cliffs eroding, her sandbanks drifting, springs bubbling up in dead ground. They regroup themselves while we sleep, the landscapes through which we move, and even the histories that trail us; the faces of the dead fade into other faces, as a spine of hills into the mist.”

During the time-freezing national lockdown from which most countries are finally beginning to thaw, the transtemporal power of literature has struck me more than ever before. The above quotation, from Hilary Mantel’s 2009 novel Wolf Hall, refers to the turbulent historical trajectory of the Tudor court in the early 1500s, yet speaks profoundly to me of my own contemporary culture in 2020.

England, and the entire world for that matter, has certainly had its fair share of “eroding cliffs” and “drifting sandbanks” in recent times, including a pandemic, riots and ceaseless political unrest. It is inevitable that, confronted by these multifarious black swans, human culture is forced to ‘remake’ itself, like Mantel’s England. But how does this ‘remaking’ affect our relationship with ‘the histories that trail us’ and ‘the faces of the dead’? In the wake of horrific police brutality in the US,

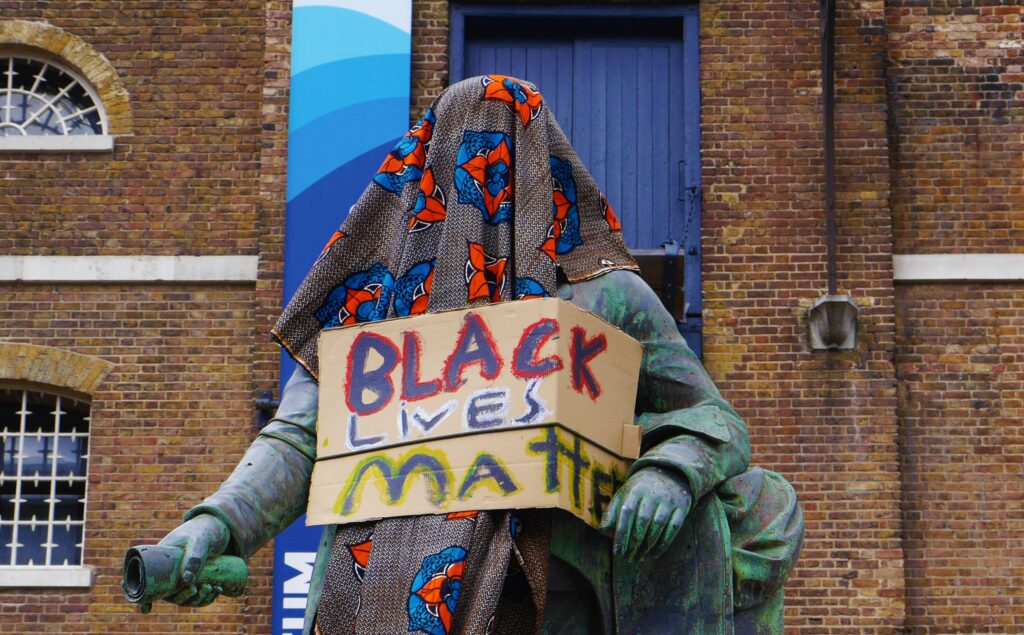

does the toppling of controversial statues really lead us towards that healthy ‘remaking’ which the whole world so greatly needs?

The question of whether it is right to tear down monuments memorialising controversial historical figures is a complex one. To my eyes, the sensationalist media continues to gloss over the deeper issues at stake, plastering our TV screens and news feeds with only a superficial understanding of the dilemma. Before signing up to the “tear ‘em down” agenda, it’s important for each person to consider the potentially detrimental impact of uprooting structures which are perceived as offensive to certain groups within contemporary society.

Those who feel intense anger and sadness as a result of injustices they have suffered deserve our fullest empathy. On a practical level, to resolve deep-set ideological problems such as systemic racism, it is necessary to tackle the root of the issue in an alleged racist institution.

Tearing down a statue is quite unlikely to help correct the day-to-day racism operating in a particular workplace, for example. There are other more efficient courses of action which should be taken in order to resolve such problems. It appears more often than not that protests petitioning for the removal of statues are therefore not really designed to be effective agents in resolving racism. Instead, it seems that these protests are part of a greater ideological desire to rebel against any established objective authority. Far from helping to ‘remake’ anything, the recent destruction of monuments in the public sphere has only emphasised social divisions all the more.

In addition to these practical considerations, I would argue that, as offensive as some of them might be (to myself included), these controversial statues are extremely important in themselves and it would be a big mistake to destroy them. While we should be sensitive to how hurtful certain historical and cultural memories can be to those whom they affect, this sensitivity should not compromise our appreciation of history’s importance.

The twofold past has happened – the past in which the original event occurred (eg imperialism), and the past in which the memorial statue (eg of Cecil Rhodes) was subsequently erected.

Both pasts are not something that can be changed. We should rather learn from them: both the initial historical event and about the society in which the event was later memorialised.

If a constituted authority decides to remove monuments, as has previously happened with statues of Hitler and Mao, some may argue that this is acceptable. Even still, I think the ‘lest we forget’ argument is a crucial one. These statues, even of the most brutal totalitarian leaders of the 20th century, are important cultural reminders that we shouldn’t make their same mistakes again. These statues should not be perceived as inappropriate glorifications, but as appropriate social deterrents. And if we don’t see these statues on an everyday basis in prominent public positions, who knows in how many years we may forget the atrocities of Nazism and Communism and, God forbid, go on to commit the same crimes, albeit under different names and disguises.

Trying to erase history by dismantling statues is also a very slippery slope. Black Lives Matter protests have threatened to tear down a statue of Abraham Lincoln, accusing him of being racist. This man actually endorsed emancipation and abolished slavery in the US. Protests in London have vandalised a statue of Winston Churchill, declaring him as a fascist despite Churchill fighting against fascism throughout his time as Prime Minister in the Second World War. However, these statue-toppling attempts threaten society with greater risks than just physical damage.

If we pull down every statue of every person from the past whom we believe might have committed some objectionable action, even though they might also have done a lot of good, we risk losing an essential capacity to make historical distinctions. Who is totally blameless? Even the most enlightened or holy figure might be objectionable to someone under some light. We really need to be able to distinguish between people who did great good, albeit with possible errors, and those who really were evil. Other liberties are also threatened: again, God forbid this should happen, but how long before certain social groups find the visual expression of religions offensive and demand that all places of worship be torn down too?

It is undeniable that many of our ancestors have caused their fellow human beings huge suffering. But it is the history of which these ancestors form part that we need to acknowledge and learn from to better stabilise and sanctify humanity in the future. If we try to erase the past and any memorial traces of this, we only wipe the slate clean to allow the same corrupt ideologies to grow again, perhaps under different manifestations. This is not to say that we cannot be sensitive to those individuals for whom particular historical moments and figures are painful cultural memories.

We should be compassionate towards one another and appreciative of the emotional resonances such monuments might provoke in some people.

Perhaps analogous to the statue controversy is a similar dispute in the humanities. Writings from the Medieval and Renaissance periods often contain contentious expressions of sexism and anti-semitism. Whilst these expressions should be deplored, they should certainly not render these writings unsuitable for study by future generations.

The counterpart to tearing down a statue might be tearing up a medieval manuscript. The problematic sentiments expressed by this literature clearly should not be condoned. But these sentiments were articulated in a particular historical context and thoughtspace from which modern-day society is far removed. And mixed with the negative, there might be many noble insights which are far richer than and superior to many contemporary expressions of thought.

Rather than censoring or totally disregarding the greatest literary masterpieces from the 7th to the 16th centuries because they fail to fit into our 21st century thinking, these controversial writings should be valued as opportunities for better understanding the nuanced historical contexts in which they were written. It would be wrong to stop imparting to subsequent generations the wisdom of Chaucer and Shakespeare because of these writers’ ‘political incorrectness’ as perceived by a scholar of the 2020s.

Maybe we need a more ‘warts and all’ approach to history. We don’t censor it, cover it up or pull it down, but we do encourage robust discussion about its rights and wrongs, while equally striving to appreciate that how we see things now is not always the correct viewpoint.

Awareness of both the context in which the initial historical controversy occurred and the subsequent historical context in which the memorial statue was erected or the text written provides copious opportunities for intellectual and social growth which it is a mistake to destroy.

So, we should not destroy these statues but learn from them: these stone landmarks are emblems of historical truths which pinpoint where the human race, both fallen and glorious, has come from and where it needs to go.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!