The poor philanthropist

Adam Brocklehurst discovers a man who sought to stay poor to give to the poor.

Hanging in Manchester City Art Gallery is a larger-than-life painting titled The Good Samaritan. It’s a fine early work by the Symbolist artist George Frederick Watts. Once considered one of Britain’s great artists, Watts’ popularity has waned into obscurity, probably due to the weirdness and obliqueness of his later works.

The Good Samaritan is a common enough, dare I say it, repetitive subject matter in art. It’s taken from the Gospel of Luke and the canvas depicts the eponymous Samaritan supporting the wounded Jewish traveller on the road as he leads him to his waiting donkey, and then on to the inn, after the priest and Levite have crossed the road and ignored the fallen man’s plight. The scripture can be read as an allegory of the passion of Christ but is probably a more direct scriptural lesson in ethics. Christ is in effect telling us what we should do were we ever to find ourselves in a similar situation.

This work, with its muscular grandeur and sepia fresco-like tones, owes an obvious debt to the work of the Italian master Michelangelo. It manages to bring home an important lesson in humility and charity without any cloying sentimentality, but with much pathos.

What is less known, however, is that this painting isn’t merely one more worthy iteration of the gospel parable. It is a tribute in oil to a very real person who incarnated the mercy which Christ encouraged in the figure of the Good Samaritan, a man who bore his suffering fellow human beings on his shoulders and found practical ways to help them: the philanthropist Thomas Wright.

chalk, circa 1850-1851

24 in. x 20 in. (610 mm x 508 mm)

Given by George Frederic Watts, 1895

Primary Collection

NPG 1016

Born in 1789 in Haddington, Scotland, to a Scottish father and English mother, Wright emigrated South to Manchester, the hometown of his mother, then the young industrial powerhouse of the British Empire. He started his working life in unpaid indentureship, with Ormerod & Sons making steam engines, gaining his training and experience through hard work and working his way up from a child apprentice to a waged man employed in heavy manual labour in front of the terrible heat of the blast furnace. He was eventually promoted to the role of foreman, a responsible supervisory position.

The world Wright knew would have been black from pollution and coal dust.

To this air pollution could be added the noise from the proximity of Cartwright’s industrial looms, then the greatest machines the world had ever known, each one working day and night to sate a seemingly inexhaustible appetite for cottons, calico, and linen. It was for this reason that Wright’s city was known throughout the world as Cottonopolis.

Wright’s formative years in the late eighteen century were not solely focused on work. He was literate, receiving a free education from the Wesleyans, or Methodists. This relatively new Protestant sect followed the teachings of the charismatic and humane John Wesley. Wesley advocated a Christ-centric practical theology which operated through the symbiosis of faith and good works, ultimately leading, he believed, to personal sanctification. These Works of Mercy included supporting the destitute in practical ways, such as free education, tending the sick and the regular visiting and rehabilitation of those incarcerated in prison.

Theoretically such a moralising ethos was lauded throughout nineteenth century society, however there was much social hypocrisy and a great distance between what was preached and what was put into practice. Society at this time was paternalistic to the extreme, and this paternalism exhibited a kind of structural authoritarianism, which was intentionally low on compassion and kindness and high on punishment.

‘Spare the rod, spoil the child’ could be applied to everyone from children in the nursery, to criminals in prison, to people suffering extreme poverty through no fault of their own.

A firm hand was applied with gusto by the state and the clergy alike, and there was a definite belief that what had befallen these people was probably their fault, their suffering seen as the result of a kind of karmic vengeance.

So, when Thomas Wright discovered that a man he was supervising was a former convict, he would normally have been expected to immediately terminate his employment (unionisation and full employee rights were a long way in the future). The foundry wouldn’t have struggled to find a replacement, life and labour were plentiful and cheap.

The impact on the man however would potentially have been massive, his home and his family were dependent on the wage he brought home. Without a job he would face destitution and the poor house, he might be tempted to reoffend, and a return to prison may have been his ultimate destination.

Instinctively Wright stepped in with a simple solution, offering to raise £20 as a bond of good behaviour on behalf of the man. This was no small act of charity; Wright was then only earning £3.6s a week and having to cover the living costs of his enormous brood of nineteen children. This generosity would be repeated again and again by Wright as he took up the welfare of both serving and former prisoners, befriending them and seeking and finding them employment, and then guaranteeing their good behaviour with his own money.

Unlike his philanthropic contemporaries Lady Angela Burdett-Coutts or George Peabody who used promotion as well as their great personal wealth to draw attention to their causes, Wright actively avoided publicising his work. Regardless, word of his work began to leak out.

He was approached by the good men of Manchester corporation and offered a yearly salary of £800 to work as the city prison inspector, nearly four times his annual wage. But Wright refused this generous offer. He understood that the reason his work was so effective was because he was not part of the hated system, that those he supported trusted him chiefly because he was a working man of their own class. Such trust was hard won and easily squandered.

By 1852 Wright’s fame was spreading further afield. He was friends with the famous Manchester-based author Elizabeth Gaskell who lived nearby his home on Sidney Street Chorlton on Medlock. She was actively seeking to raise a pension for the now elderly Wright.

Now in his 60s, the philanthropist was still working over 12 hours a day in the foundry. Gaskell’s friend Charles Dickens stepped in in his role of journalist and published a lengthy epistle in praise of Wright in his Household Words magazine, titled An Unpaid Servant of the State. In the end £3,248 was raised to allow him to retire and focus fully on his charitable work. That same year the young artist George Frederick Watts, ‘as a testimony’ to his esteem for Wright, presented his painting, The Good Samaritan, to the Corporation of Manchester. It remains a fitting memorial to one of our great unsung philanthropists and a great antidote to the lie that there is nothing we can do to improve the world we live in.

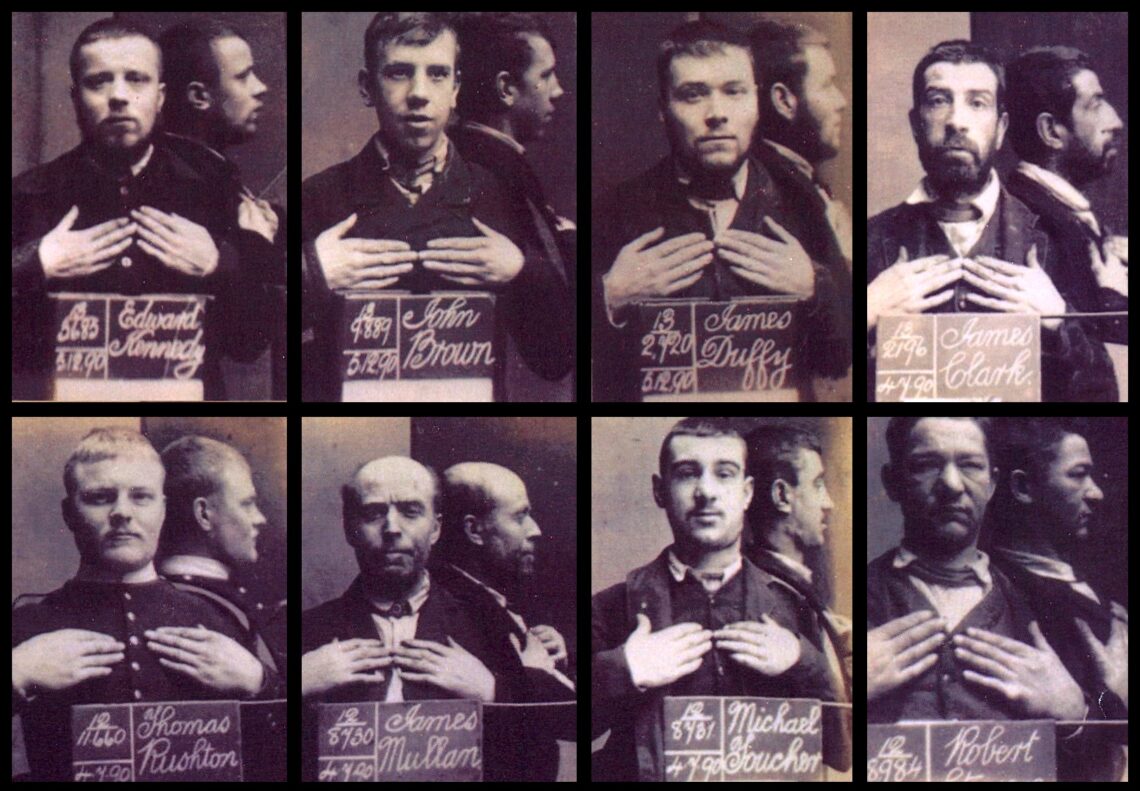

Featured image credit: “Barlinnie boys” by angus mcdiarmid is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Adam Brocklehurst

Adam Brocklehurst is a writer for Adamah Media. He graduated from Luther King House in association with the University of Manchester with a Masters in Contextual Theology, after undertaking his Bachelor’s degree in History Theology and Ethics at Bishop Grosseteste University Lincoln, and did much better than he or anyone else expected.