Hope for victims of divorce

Reading Lord of the Rings helped Alexander Wolfe find ways forward for adult children suffering from their parents’ break-up.

It is not uncommon for children of divorce to feel a false sense of guilt related to their family’s fracture. For some, this takes place at a moral level: we feel like we did or said something (or failed to do or say something) that contributed to the breakdown of mom and dad’s relationship.

For others, the guilt is located at the ‘ontological’ level, which is to say, the level of being: we think, “Before I existed, mom and dad were happy together. Then I came along. And now they’re getting divorced. It’s not anything I said or did – the problem is that I am.”

I have felt guilt at both levels, although in a different way. First, rather than feeling guilty for my parents’ divorce, I felt like it was my fault that they got married in the first place: I was conceived out of wedlock.

I used to think: “If I had not happened, my parents would probably have gone their own ways. But I did come into being, and instead they got married and had more kids before separating. If it weren’t for me, everyone would have been spared a lot of trouble.” On top of that, I was literally the ring-bearer for my parents’ wedding when I was four years old, so I felt like I had caused this in an active way as well.

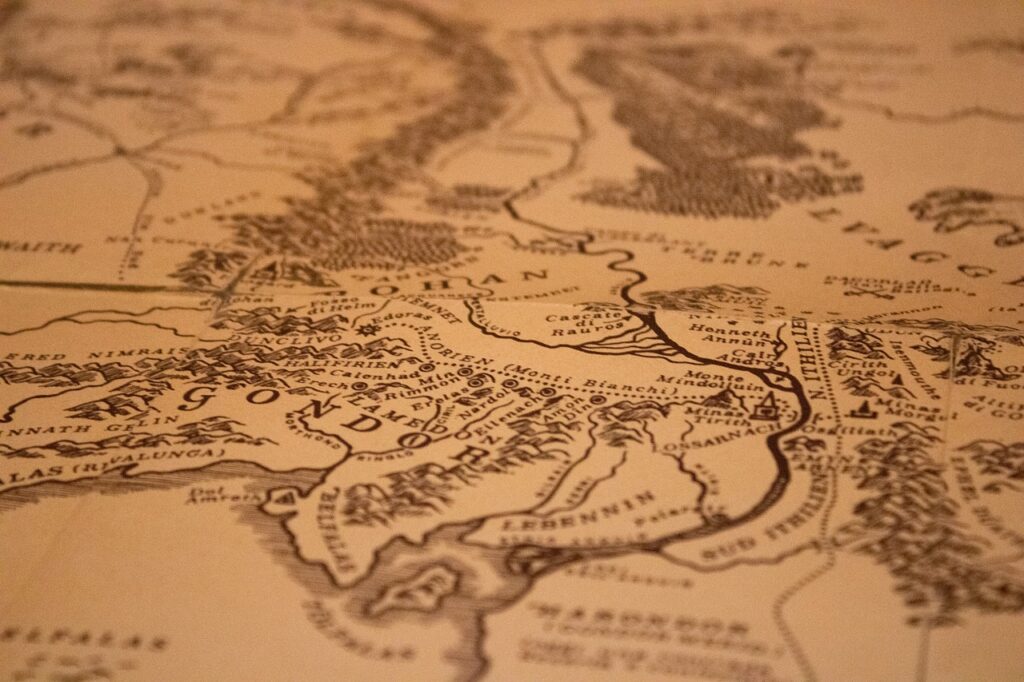

Thanks to my spiritual director / counsellor and the Life-Giving Wounds community, I have been able to find freedom from this false sense of guilt. Still, it was a weight that I carried for a long time. I was inspired to re-read The Lord of the Rings specifically through the lens of this experience, especially since Frodo is also the ‘Ring-bearer’. I finished this project recently and I wanted to share my reflections with you here.

First, a few disclaimers. 1.) Although I will be placing us in Frodo’s shoes, I am not saying that our parents are the evil lord Sauron. As always, in this ministry, we are not so concerned with casting blame on other people as we are about taking account of how we have been affected and how to get better. 2.) I am also not claiming that The Lord of the Rings is only about parental divorce. Great art is rich with meaning, and this novel is so symbolic that its story can touch on many different aspects of the human experience. That being said, let’s get started.

When the ring is passed down to Frodo – after Bilbo makes his dramatic birthday party exit – he finds himself in danger. In the Peter Jackson movies it is almost immediate, but in the book he has the ring for 17 years before the Black Riders appear in the Shire. In any case, Gandalf advises him to flee his home and make his way to Rivendell, a magical Elvish otherworld, where he will be safe. There is not much in the way of a game-plan, nor is there a clear path – all that was important at that point was that Frodo should leave home and get to safety.

This moment in the tale can represent for us the immediate aftermath of our parents’ divorce. Home has come under attack, and we cannot stay.

We have no clear idea of what all is unfolding nor where this will lead us. We can figure things out later, but at this moment we are just in threat or survival mode. For some, this was a short phase; for others, it lasted years.

Once Frodo makes it to Rivendell, the elf lord Elrond calls a council to decide what must be done about the ring. This moment can represent for us the reality that, even though we may have survived the divorce, we still have to decide what exactly we will ‘do’ about this wound and its effects: the sense of guilt, the identity crisis, the struggle with faith, the problems we experience in love and relationships, etc. The options presented at the Council of Elrond have a certain correspondence to what we take to be our own options.

One suggestion is that the ring be given to Tom Bombadil. Bombadil unfortunately is not portrayed in the movies, but he is a jolly forest-dwelling character over whom the ring has no sway. Many times, as adult children of divorce, we try to convince ourselves that our parents’ divorce does not affect us or has no sway over us.

What’s interesting is that the council decides not to give Bombadil the ring because he would soon forget it, or most likely throw it away; he would be a most unsafe guardian. Likewise, if we try to pretend that we are in no way affected by our parents’ divorce, this is precisely how it can continue to be dangerous. The wound would still be operative; we would just be living in denial.

Another suggestion is that the ring be sent over the great sea. This is not a realistic option for the ring because the people across the sea would never accept it; they would see that it is a menace for the people of Middle-Earth, and so they would not want that trouble to plague them as well. I think this option can represent for us divorce victims the tendency to try to work around the problem of our parents’ divorce. We realise that, yes, it hurts and causes a lot of problems, but rather than confront the wound head-on, we adopt coping mechanisms or treat it at a symptomatic level.

Reading the chapter about the Council of Elrond was really interesting; they really do not want to conclude that the ring must be dealt with. I think many of us in the Life-Giving Wounds community can say that we, too, have experienced a decisive moment when we kind of knew that we should go to counselling or attend a retreat, but we really tried to convince ourselves to not go. We think, as a friend of mine once put it, “I can’t deal with my parents’ divorce; that’s a load-bearing emotion! I had better stay away from it or else I will crumble.” I know I felt this way. (And, as I wrote about here, this feeling might be more common among men than women.)

I also want to mention that the only other ‘option’ is to use the ring, but we see what doing so did to Smeagol: he is consumed and warped by it.

Too often, people who are deeply hurt by mom and dad’s divorce end up defending, ironically, a so-called ‘sacred right to divorce’.

Rather than seeking the truth about marriage and healing from their wounds, their thinking becomes twisted and divorce becomes the paradigm. Gollum is tortured by the ring and is betrayed by it over and over again, yet he can’t but crawl back to it. It’s all he can see. This is clearly not the way forward and upward.

The Council of Elrond concludes when Frodo takes ownership and courageously steps forward: “I will take the ring to Mordor, though I do not know the way.” The others are inspired and pledge to go with him.

If there are two things we learn from reading Lord of the Rings, it is that we always need help and that there is always hope. Samwise Gamgee can represent for us a particular friend who is our closest companion in the healing journey (“I can’t carry the ring for you… but I can carry you!”), and perhaps the Life-Giving Wounds community can represent the fellowship which knows the Way.

Ultimately, Frodo and Sam arrive at the Cracks of Doom and destroy the ring – with a little help, surprisingly, from Gollum. The journey was not without its temptations, setbacks, losses, desolations, or betrayals, but the ring is eventually cast into the fire. What happens in Frodo?

“‘Well, this is the end, Sam Gamgee’, said a voice by his side. And there was Frodo, pale and worn, and yet himself again; and in his eyes there was peace now, neither strain of will, nor madness, nor any fear. His burden was taken away. There was the dear master of the sweet days in the Shire. ‘Master!’ cried Sam, and fell upon his knees. In all that ruin of the world for the moment he felt only joy, great joy. The burden was gone. His master had been saved; he was himself again, he was free.”

Let’s draw to a close. In the movies Frodo and Sam go back to a peaceful home, but in the books it is not so. They go back and the whole place looks foreign to them. As it turns out, Saruman escaped from the ruins of Isengard and has been wreaking havoc in the Shire: he tore down old houses, ripped up trees, let the land fall into ruin, and the people who remained were living in fear and suspicion.

It is not as though, once we confront our wounds, everything will go back to the way it used to be.

Mom and dad ain’t gettin’ back together. But this does not mean that the quest was in vain or that there was not great healing.

The absolute final moment of the novel is the departure of Frodo and Gandalf for the Grey Havens, a quasi-heavenly realm, the ‘undying lands’. Sam (who by this point is married and has children) is confused why Frodo does not want to remain in the Shire. Frodo answers, “‘I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: someone has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them. But you are my heir: all that I had and might have had I leave to you.’”

I love this ending! Frodo’s whole quest, at its very end, was not merely something he carried out for his own gain; rather, his quest was a generous one. He saved the Shire not so much so that he could enjoy it, but so that the next generation can.

In a similar way, our own healing journey is generous: our quest is undertaken so that our children might have what we did not: namely, an intact home.

If you are ever tempted to think that going to counselling or going on a retreat is selfish, remember first of all that you are worthy of the great gift of being healed, and furthermore that this quest is not only for your own personal salvation but, in a mysterious way together, for the salvation of the world.

This is a slightly edited version of an article which first appeared on the https://www.lifegivingwounds.org/ website. It is republished here with permission. For the original article, see here.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Alexander Wolfe

Alexander Wolfe received his education from the Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and the Family in Washington, D.C., and he is the Assistant Director of the Office of Marriage, Family, and Respect Life at the Catholic Diocese of Arlington (Virginia). Alex is also the Chapter Support Lead for ‘Life-Giving Wounds’, a American non-profit dedicated to the healing of adult children of divorce. In his free time, Alex enjoys playing the guitar, visiting Italy, and following professional footballer Lionel Messi.