Portraits of beauty and corruption: the danse macabre of the Countess of Castiglione

Adam Brocklehurst comes face to face with the disfiguring power of time.

We all have that person in our lives who fascinates us. Sometimes it’s a fascination drawn from admiration, other times it’s simply curiosity about a life lived differently to our own.

When fascination ‘strikes’, we gobble up everything we can find about that individual, seek out their biographies, and even plan a pilgrimage to areas associated with them.

This was the case with me when I stumbled across the Countess of Castiglione 20 plus years ago whilst rooting through a bookshop in West London. It was an expensive and glossy coffee table book titled, “La Divine Comtesse”: Photographs of the Countess of Castiglione, which had been published to coincide with an exhibition of her photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, way back in September 2000. I saw it and that was it. I was smitten.

Page after page of the heavy book are filled with depictions of a pale and statuesque, rather melancholy looking woman, expensively dressed, with complex coiffures, and voluminous low-cut gowns. In retrospect it was probably the fashion that drew me to her. I’ve been interested in historical dress since I was a child, a fascination which has proven very useful in my later career as a historian when dating images.

What is peculiar about the photographs is the element of fantasy that weaves its way through them. In one tinted photograph the countess flees an imaginary ball, in another she leans provocatively over a chair dressed as an 18th century French aristocrat. We even have her garbed in the habit of a Carmelite nun.

Virginia Oldoini was born in 1837 into the lower ranks of the Florentine nobility, into a family of diplomats.

Her almost preternatural beauty, high intelligence, alongside a certain ruthless streak and innate immorality, brought her to the attention of those shadowy people in secretive governmental organisations who can put such facets to best use.

Soon she was embroiled in an affair with the dissolute Victor Emmanuel II, King of Sardinia, and reporting everything that occurred between them, in her carefully coded fine cursive script, to her cousin, the great Piedmontese statesman and nation builder Camille, Count Cavour.

Eventually moving to Paris with her much older husband, the Count of Castiglione, ostensibly part of a diplomatic mission to promote Italian interests, she quickly divested herself of her bewildered spouse, and set about her real purpose in travelling, by seducing the French Emperor Napoleon III.

When her influence very feasibly brought the Unification of Italy a little closer to reality, she was not yet 20. In the years ahead popes, kings, generals and great financiers called upon her unique skills and connections to further their ambitions.

She really was the original Bond girl, a femme fatale of Second Empire France.

Had this been the sum of her abilities, she may have warranted a piquant line or two in one of the many histories recording the tectonic shift of the great plates of Europe in the late 19th century, as it moved from a land of kingdoms and principalities to one of great nation states. Turbulent times throw up such people, and nation building is rarely achieved with clean hands.

But it is not her political machinations that have placed her amongst the more remarkable women of the 19th century, rather it was what was for her a private pastime, a hobby if you will, though on a grand scale, something indulged in purely for her own pleasure, that she is remembered.

When Castiglione first approached her lifetime collaborator, the Parisian high society photographer Louis-Pierre Pierson in the early 1850s, photography was still a relatively new medium. Its most obvious use was simply to produce a conventional likeness, and it was for this purpose that she initially sought him out.

Castiglione, however, soon began to make unusual requests. She directed Pierson to record and re-record her social triumphs at the various courts she had graced, wearing the same grand apparel. Then she moved away from reality towards imaginary scenarios, scenes and characters from plays and operas she admired, Verdi’s Violetta, Anne Boleyn, even mimicking the great Italian stage actress Adelaide Ristori.

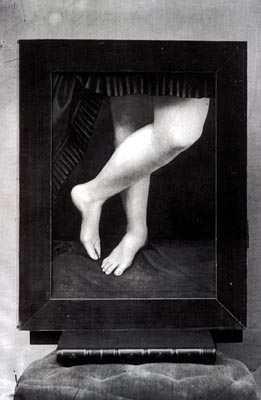

She becomes increasingly obsessive with the individual facets of her beauty, her foot, her ankle. In probably her most famous image, the iconic Scherzo di Follia, a black and white photo, one graceful arm holds a picture frame, isolating a single eye, turning the tables on those who ogled her, she haughtily appraises her audience.

Eventually the countess produced a vast catalogue of such images dedicated purely to her self-devoted one-woman cult.

Unwittingly, she may have been the first woman to direct in front of a camera, albeit a static, photographic one. Likewise, she was perhaps the first to direct a mise-en-scene. Without her distorted, fragmented sense of self might the surreal and psychological elements of photography have been somewhat slower in making their presence felt?

The 20th century photographic masters, Man Ray, Cindy Sherman or Nan Golding all owe a debt of gratitude to the rather self-obsessed Italian. She influenced the taste of American Vogue’s legendary Diana Vreeland and was pivotal in the development of the style of the renowned photographer Richard Avedon. When Abigail Solomon-Godeau wrote the Legs of the Countess in 1986, she earned her place in the canon of Feminist and Postmodern Theory.

It is in today’s society that we see the prescient nature of her work most clearly, in the growing obsession with the self and physical form. Endless faces turned blankly upwards towards the camera, lips pouted, heavily made up, artificial, waxy, repeated again and again ad nauseum across social media.

Spontaneous snapshots are now replaced with carefully constructed Instagram set pieces created to display wealth, draw envy, flagrantly flout the Seven Deadly Sins, and record the fact in perpetuity.

Perhaps most disturbingly of all, the countess hits us with the reality of what all this means, what the ultimate outcome will be for every one of us.

After a hiatus of decades, she returned to Pierson, her erstwhile collaborator, for one final session. The camera, now her mortal enemy, is pitiless in its honesty. The smile that once entranced kings is a death’s-head grimace.

She leers at us, parodying the voluptuous poses of her glorious youth. A raddled and ancient courtesan, still in the same tattered ball gowns she had worn 40 years earlier, her charms are now entirely moribund. She has become the fabled mad woman in the attic of Victorian literature, an insane Mrs Rochester had she lived long enough to enjoy her addled dotage.

That’s perhaps what we should take away from the portraits of this strange woman, that we live a dance macabre. The selfie-obsession of our salad days may return to haunt us, when the vagaries of life tarnish the vivid sheen of youthful beauty, and the hair greys and the eyes dims.

Castiglione reminds us, with some brutality, where we are heading, and it’s not pretty. It’s up to each one of us to choose to take heed of the warning present there, though time itself has a mind of its own and may very well disregard our wishes.

So instead of time wasted curating our own online image, perhaps we should take a moment to seek out what matters, to look inward and cultivate kindness and a good heart, both traits unlikely to ever lose their lustre.

Featured image credit: Countess de Castiglione as the Queen of Etruria – photograph by Pierre-Louis Pierson, painted and retouched by Marck (MET, 2005.100.410 (3a)) (with the hyperlink https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/288157)

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Adam Brocklehurst

Adam Brocklehurst is a writer for Adamah Media. He graduated from Luther King House in association with the University of Manchester with a Masters in Contextual Theology, after undertaking his Bachelor’s degree in History Theology and Ethics at Bishop Grosseteste University Lincoln, and did much better than he or anyone else expected.