Nigeria’s lights and shadows: finding hope in a sea of fanaticism and secularism

Joshua Nwachukwu looks at the challenges overlooked by western commentators in the ongoing battle for the soul of Africa.

Earlier this year, on January 20, Rev Lawan Andimi was beheaded by the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram after having been abducted 18 days earlier. Prior to his death, he had been the chairman of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) in Adamawa state, Nigeria. CAN is the umbrella association of Christians in Nigeria.

Andimi’s death was, alas, not an isolated one. For many years, thousands of Nigerians have been killed, attacked and assaulted by Boko Haram. Properties, businesses and communities have been destroyed. Churches and markets have been bombed. Apart from its semi-military operations, Boko Haram has also resorted to mass kidnappings and extortion to replenish its funds and ranks. It has also engaged in forceful conscription of new fighters, including child soldiers.

Despite claims by the country’s leaders that the terrorist group has been defeated, the reality on the ground is very different. This banditry is a more threatening pandemic to us than the Coronavirus.

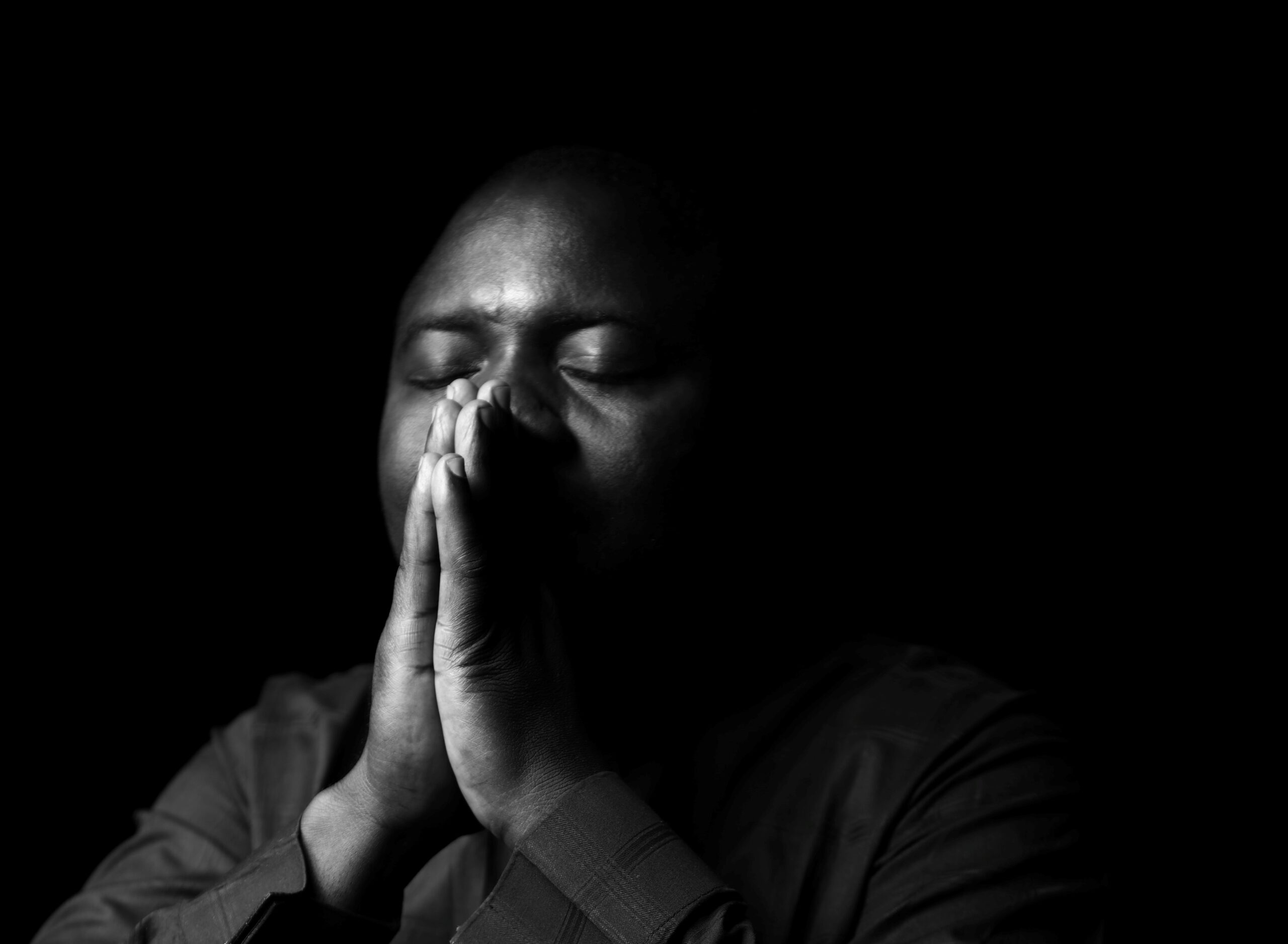

Andimi fascinated the world with a video he made prior to his beheading. In the proof of life video, Rev Andimi, without any sign of losing his peace and tranquillity, asked his colleagues and particularly the president of his own denomination, to speak with the Adamawa state governor and other relevant officials to secure his release, adding “don’t cry, don’t worry and thank God for everything.”

Despite being held captive, he commended his attackers for feeding him well and for taking care of him.

Furthermore, while expressing confidence that “by the grace of God” he might return to family and colleagues, he added:“If the opportunity has not been granted, maybe it is the will of God.”

These words coming from a man hours away from death sent shockwaves around the country. Christians and other people of faith were struck by his serenity and sense of the Divine.

Rev Andimi is not the only hero in this sad episode: his wife also surprised many. When later asked how she felt about her husband’s death, she too was calm, expressing her happiness that her husband did not deny Jesus and her delight that he was with God.

This video shows the heroism required by people of faith, particularly in Northern Nigeria, to exercise their freedom to worship. Many, despite the persecution, have remained strong and indefatigable.

The video also shows the power and effectiveness of forgiveness and non-violence which Christians have adopted over the years as their only weapon in the whirlwind of religious persecution. Non-violence has helped maintain co-existence in Nigeria.

But more importantly, the video, with the concluding words of Rev Andimi: “Don’t cry, don’t worry, but thank God for everything”, has inspired many, displaying a positive approach to life: when things are going well or badly, in sickness and in death, or even facing the Coronavirus pandemic.

The secular nature and peace of Nigeria remains, however, threatened by Boko Haram which seeks to overthrow the Government and create an Islamic state.

It promotes an extremist version of Islam which makes it “haram”, or forbidden, for Muslims to take part in any political or social activity associated with Western society.

Boko Haram opposes voting in elections and secular education. The organisation’s name, Boko Haram, loosely translated means “Western education is forbidden”. Little wonder its members have attacked schools and kidnapped students, most notably the Chibok girls.

Despite the fact that Nigeria has been ruled mostly by Muslims, who have held most top governmental positions, the extremists are not appeased or convinced. Rather they regard the Nigerian state as being run by non-believers, regardless of whether the president is Muslim or not. While their victims have been people of different faiths, Christians are the worse hit. An estimated 1000 Nigerian Christians were murdered in 2019 while some 6000 have been killed since 2015.

This situation has sown seeds of mistrust between Christians and Muslims, who make up the two dominant religious groups in the country. While the Christians accuse the Muslims of complicity by not forcefully calling out the extremists and fanatics who engage in genocide against Christians, the Muslims have accused the Christians of inflaming religious vitriol by such accusations. This accusation and counter-accusation, rather than heal the society’s divide, merely worsens it. Apart from being a religious issue, Boko Haram now has political, social and economic underpinnings.

In addition the banditry of Boko Haram has had several unintended consequences.

Christians hear, almost daily, of heroic acts of their fellow believers who want to express their faith.

Some Christians go as far as defending their churches when they hear of a threat of imminent attack. Some others go back to their churches to worship immediately after its destruction.

A friend of mine some years ago had to travel to a state in the north of the country for work reasons for a few months. While he was there, he interiorly excused himself from attending religious activities and justified his decision under the guise of not wanting to be attacked while in the church. To his chagrin, he noticed a female colleague who went frequently to church. Once he stopped her to inquire why she went, despite the inherent dangers. She said if she was to be attacked while she was in church, this would be the best place of all to die.

This answer exposed my friend to the deep faith many of the northern Christians have and the level of detachment they show with regards to their life and plans. It surely propelled him back to the practice of his own faith.

While some have been reinvigorated in their faith, others, especially those schooled in western universities or exposed to western media, have extended their disenchantment with Boko Haram and the ills it has brought to a distaste for all religion. This has heightened the discussion and public anxiety about the deadly consequences of religious fanaticism.

Thus, the narrative is spreading that, rather than being a good for society, religion is a danger – irrational, divisive and violence prone. People quote the famous British atheist Richard Dawkins, who said: “To fill a world with religion, or religions of the Abrahamic kind, is like littering the streets with loaded guns. Do not be surprised if they are used.” Hence, rather than respect and promote faith, it is seen as something that ought to be feared and neutralized.

Now the discussion, which was originally focused on “Islamic religious fanaticism”, has subtly changed to “religious fanaticism” and eventually simply “religion”, and this worries a lot of people. Rather than genuine engagements on how to tackle the crisis, some are exploiting it to disparage religious people in order to discredit their stance in the public square.

It is a truism that both religion and science can spawn monsters and they should not be judged by their pathological forms.

While we seek ways to overcome this persecution by demanding the government secures people’s lives and properties, we take solace in Rev Andimi’s last words: “Don’t cry, don’t worry, but thank God for everything.”

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

2 Comments

Ikuku

Beautiful written, thought provoking and evoking piece

Felice Hazlegrove

hello there, your post is very good.Following your posts.