#GiveWork, not aid, to the poor: the remarkable legacy of Leila Janah (1982-2020)

” The greatest challenge of the next 50 years,” said Leila Janah, ” will be to create dignified work for everyone … not through handouts and charity, but through market forces.”

Tulika Bahadur describes the brief but extraordinary life of a woman who insisted that the poor should be empowered, not given donations.

The tragic early death of American social entrepreneur Leila Janah robbed the world not just of a talented thinker and pioneer, but also of a champion of social justice. Her vision of a reconfigured capitalism which invites the participation of the poorest of the poor is taking root, and will likely be her legacy.

The passing of this 37-year-old luminary earlier this year caused many to fear her unique insights might be extinguished. Yet such was the force of the popular Indian American that her ideas may still come to fruition after her death.

Leila firmly believed that we are fundamentally and ultimately empowered through work alone. She found a way to train and plug into the global digital economy thousands of talented and diligent people struggling with poverty solely due to geographical isolation from well-paying jobs.

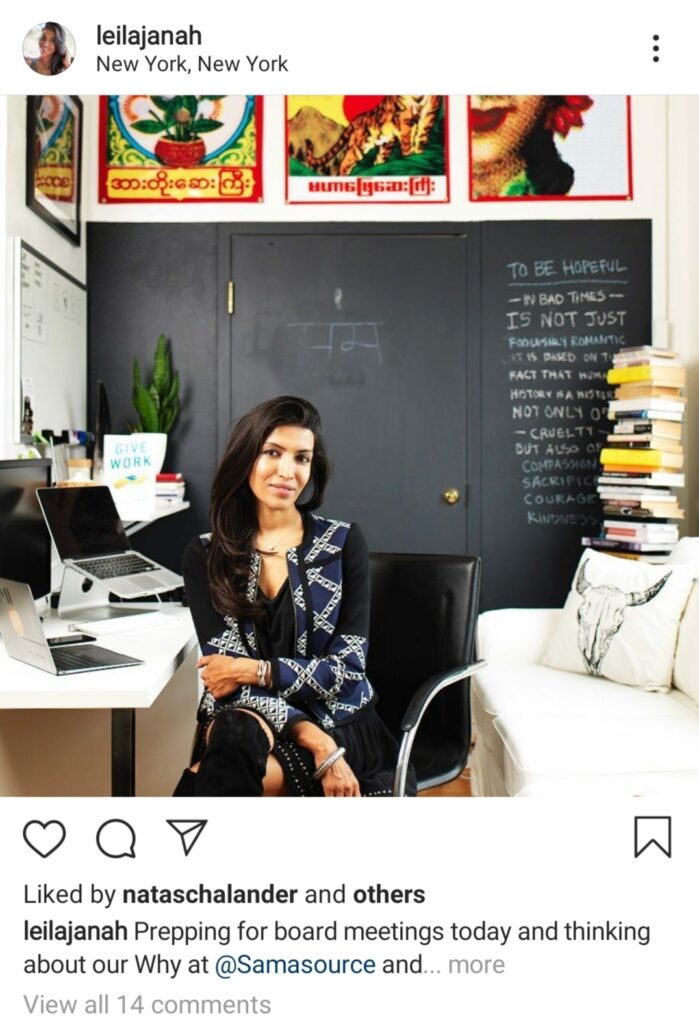

I first encountered Leila Janah in mid-2018 when she was recommended as an influencer whom I might be interested in following on LinkedIn.

A cursory scroll down her profile got me immediately intrigued. She was then a 35-year-old upstate New York-born, San Francisco-based, social entrepreneur who had founded two organisations (one related to tech, Samasource, and the other, LXMI, a beauty brand) with the common mission of giving employment to some of the poorest people in the world — and this through an innovative approach that went beyond traditional “international aid”.

As likely to be seen on the front cover of a glossy magazine as behind a desk, Leila was no ordinary businesswoman.

Prior to her entrepreneurial career, she had worked as a management consultant for a firm called Katzenbach Partners (now Booz & Co.) run by former McKinsey employees, and had been a Visiting Scholar with the Stanford Program on Global Justice. She held a BA in Development Studies from Harvard, and was a TED Fellow and a Global Young Leader of the World Economic Forum.

I needed to read several interviews to truly grasp the magnitude of labour and struggle that lay behind her impeccable CV and her adventurous globetrotting life. As I learned more and more about her, I discovered an extremely uncommon global thinker who could make connections across very different geographies and cultures.

She was incredibly articulate, ambitious and knew exactly what she wanted to accomplish and why—somebody whose progress I wanted to witness over the next 50 years. Alas it was not to be…

Janah was a pioneer in the field of “Impact Sourcing” — a form of outsourcing conducted not to exploit cheap labour in distant lands (which, unfortunately, can be found everywhere from fashion to electronics to farming) but to consciously tap the potential of low-income communities and improve their standard of living.

She had conceived a cutting-edge cross-continental business model over the previous 10 years, and she wanted to apply it to several industries over the course of her life to lift as many people as possible belonging to the “bottom billion”. She had dozens of GoDaddy domains registered.

Regrettably, Janah died on January 24, 2020 due to complications from Epithelioid Sarcoma, a rare form of soft tissue cancer. The news of her death was not unexpected but it was profoundly upsetting for me to see such a dynamic visionary pass away so prematurely at the very moment when she was only beginning to get the recognition she deserved.

As soon as I learnt that she was no more, the first thought which ran across my mind was—she was exactly the kind of individual our world needed, and desperately so. I had just interacted with her once—on Instagram, and in passing, over a post of hers on a controversial chapter of Churchill’s first tenure as Prime Minister—the claim that the careless colonial policies of his administration had contributed to the Bengal famine of 1943 resulting in some three million deaths.

Even though I had observed Janah’s life and work only from a distance and had no real contact with her, she made a tremendous impression on me—because she was a doer. Way too many people talk way too much about what’s wrong with the world, particularly in our digital age with its explosion of communication devices and platforms. Ideas and opinions are cheap.

Diagnosing problems isn’t all that difficult. There are countless notes of indignation, fervent calls for a reckoning. But it is the execution of solutions that is rare, demanding costs that few are ready and willing to pay.

As a Founder, and despite having faced considerable resistance, Janah was able to change the lives of around 50,000 people caught in circumstances of unthinkable scarcity offering them dignified employment.

As much as I find her early demise saddening, I am also glad that she left behind an invaluable blueprint for poverty eradication—well explained and demonstrated—the fundamentals of which, if understood correctly, may be adopted by just about anyone, within and across national borders, who is genuinely interested in making the world a fairer place. But before I get into the influences behind and specifics of Janah’s model, I want to highlight the problems with “international aid”—still the dominant method by which we try to tackle global inequality— problems that she was responding to and urgently wanted to rectify.

The limitations of aid

The vast majority of us have been brought up in economic contexts that sharply divide the profit and non-profit sectors. For one sector revenue must be pursued aggressively, financial targets be met and growth attained at all costs. For the other it’s all about charity, fundraising initiatives for good causes, donation campaigns, philanthropy—everything that must be done to help the needy, the marginalised and underprivileged. The ethical and social considerations which crop up in the second arena aren’t an inherent part of the first. The second begins when the first has ended, we are made to believe.

Businesspeople, while they are making their money, do not by default feel driven to save the world. But after the profits have been satisfyingly distributed among owner and employee, a certain amount may be withdrawn and given away—we take the profit/non-profit dichotomy and its sequencing for granted, hardly ever pausing to scrutinise and question it.

With the post-war rebuilding of Western nations—and following the Marshall Plan —“international aid” became a big, organised undertaking, the norm by which the haves would assist the have-nots. Vast sums of money and goods continue to be transferred from wealthy to poor countries, via governments, private enterprises or individuals (after having themselves achieved all the financial and material security they desired in their own territories).

Straightforward acts of charity are, understandably, required in some situations—for medical procedures, in wartime, for disaster relief, to rescue those on the brink of starvation, to comfort the disabled and the elderly, to provide for orphans. There is no substitute for it in extreme and immediate suffering.

But aid is not an effective long-term strategy to catapult communities out of poverty.

It has been estimated that over the past 70 years Africa has received at least $ 1 trillion in help. Many would argue that we haven’t heard stories of development and progress from the continent that can match this enormous amount.

Even the most well-meaning examples of charitable giving have limitations. Donations are, obviously, infrequent and unpredictable and cannot be relied on for sustenance; they evaporate too soon. Second, if they do become regular, they can generate a negative attitude of dependency and may leave little motivation in the recipient to take things in their own hands and assume a state of self-sufficiency. Then, there is the massive problem of corruption, with officials continually misusing funds. Also, material donations from the West (typically clothing and food grains) often cripple local industries. All in all, it would not be very wrong to say that, broadly, the positive consequences of aid are overrated. Somehow it is always too little, too late. It sometimes even helps the donor more than the recipient—as a convenient post revenue CSR and image-building activity at home.

Janah’s business models — rationale and concept

Janah believed that by continually offering handouts to citizens of poor countries who were physically healthy and mentally sound, richer nations were “writing off their dignity”, they were not treating them as “equal participants in the economy”.

To circumvent the limitations of aid, she proposed a bold, radically disruptive business model—an overlapping of first-world for-profit processes and non-profit causes aimed at the third world. She wanted businesses to involve the poor in workflows of wealth creation—as sellers of services or products—non-exploitatively.

In the mid to late 2000s, such an approach didn’t make much sense—for the logic of “social enterprises” and “benefit corporations” was still embryonic. As Janah started pitching her ideas in Silicon Valley—while surviving on ramen on a generous ex-boyfriend’s futon—she wasn’t very well received.

The obvious question was this: the poor do not have much education or many skills—what sort of useful work might they be able to offer to the global economy that could significantly improve their standard of living? Janah’s solution was two-fold. She began Samasource for impact-sourcing specific “services” of the poor, and “LXMI” for impact-sourcing certain types of “products” from the poor.

Samasource was built around the idea of breaking down large data projects of tech companies (for instance, training of AI systems) into small, doable tasks called “microwork”, which could actually be accomplished with basic literacy, numeracy and digital knowledge.

Samasource has grown to attract clients like Microsoft, Facebook, Glassdoor, Google, Ford and Getty—and it serves these giants via workers who might be operating from computer centres in places such as rural Uganda.

“Sama” comes from Sanskrit and means “equal”. The word is also the etymological root of “same” in English.

(A related project, Samaschool, was started later to train the poor in the developed world. This was conceived when Janah received negative feedback from an angry jobless man in Ohio, who complained that by giving employment to those far away in Somalia or Syria, she was betraying her own countrymen and women struggling to make ends meet.)

The second organisation LXMI (pronounced luxe-me)—named after the Hindu goddess of prosperity and beauty Lakshmi—impact-sources skincare ingredients (like nilotica, a cold-pressed butter obtained from nuts in the Nile River Valley and raw oils in the Amazon) from naturally rich but economically backward regions and sells them as luxury cosmetics in wealthy markets.

Multiple observations, realisations and influences had fed into Janah’s social entrepreneurship. Firstly, she herself knew what financial insecurity felt like. Her parents had migrated to the US from India in the 1970s and moved around a lot before acquiring a certain amount of stability.

She found refuge in learning and learned to hustle in order to survive—tutoring kids from well-heeled families, cleaning toilets at Harvard. She got to live both sides—material lack but also the realisation of the American Dream. One might come from less, she came to believe, but could change one’s fortunes by making an effort when presented with the right opportunities.

A life-changing event took place when Janah was 17. Having graduated early from high school, she won a scholarship—from all places, a tobacco company—to volunteer in a Ghanaian village as an English teacher. At that moment, she wasn’t “hell bent on saving the world” but what she discovered “blew up her mind”. Her students, some of whom were blind, were familiar with the BBC and Voice of America, and were updated on global politics. Bright and motivated, they were in many ways more aware than her peers in California—but they also happened to be living in the most abhorrent conditions she had ever witnessed simply due to an accident of birth.

It was here that Janah understood that the concept of meritocracy wasn’t applicable everywhere, that sometimes you could work hard and still not escape poverty, that talent was everywhere but opportunities were clearly not.

Post-Harvard, while she was placed in Mumbai as a management consultant for the outsourcing industry, she learnt that one of her employees commuted to work from his home in the slums everyday by rickshaw. She thought: what if we could locate a call centre in the slums? And the moment sparked the idea for Samasource.

When she went back to America, she began working further on her concepts, living minimally and cutting expenses wherever possible. Her first round of funding came from Amsterdam—she entered a competition for a business plan conducted by the Dutch Postcode Lottery and was granted 22,000 Euros.

Some of the thinkers whom Janah drew upon included the American political commentator Thomas Friedman (who authored The World is Flat, about globalisation), Bangladeshi economist and Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus (who pioneered the concept of microfinance) and the American venture capitalist Ben Horowitz (who talked about the importance of “not giving up” for entrepreneurs in his book The Hard Thing about the Hard Things).

She would, not uncritically, read many philosophers on justice and altruism, like John Rawls and Peter Singer. Wherever she felt something was missing in the thoughts of the people she engaged with, she added her own unique approach.

For example, she felt that there was one problem with Muhammad Yunus’ microcredit framework. Let’s say that a woman in a village gets a small loan to start a business…who will be her customers? Most likely other poor people. How will her standard of living improve then? It couldn’t, Janah ascertained, unless money was injected by an external, richer force.

That’s why she was so determined to link her slum-dwelling African trainees to clients not in Africa but America. That way she increased their income by 400% – from two dollars per day to 10, enabling them to buy protein and fresh vegetables, and pay for their children’s school fees.

In no small part was she inspired by the pivotal figures of Catholic Social Teaching. She was not officially a Catholic but she revealed in an interview that she was “raised in that kind of environment” and faith was an anchor to her. Her father had received a Jesuit education in India and her domestic context had equipped her to spot injustice from an early age.

Over the years, she had immersed herself in the writings of many faith-based leaders and activists—Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day, Sister Helen Prejean, Martin Luther King Jr, Paul Farmer and others.

In her book Give Work: Reversing Poverty One Job at a Time (2017), Janah quotes from Pope Francis’s exhortation Evangelii Gaudium (2013): “Welfare projects, which meet certain urgent needs, should be considered merely temporary responses. As long as the problems of the poor are not radically resolved by rejecting the absolute autonomy of markets and financial speculation and by attacking the structural causes of inequality, no solution will be found for the world’s problems or, for that matter, to any problems. Inequality is the root of social ills.”

Janah took the Pope’s assertion as a call for the reformation of capitalism—a process in which she considered herself an active participant.

What I find interesting about Janah’s thinking is precisely this—her intention to reform capitalism to make space for the poor. There are plenty of lively intellects who, frustrated with inequality, sing a predictable refrain—criticising the rich for their selfishness, pitying the poor for their haplessness and in the middle of it, attacking governments for their incompetence.

When they see market forces running riot, and excluding and displacing those with few means, they wish there was a cap or lid on capitalism; they see it as a beast and want to beat it up. I’m not convinced such rhetoric is very helpful.

Firstly, the rich are not likely to magically undergo a change of heart and share what they have accumulated for free. Next, if we discourage wealth generation in the name of a more equitable redistribution of resources, we run the risk of dampening the entrepreneurial spirit—which is never healthy.

The poverty alleviation solution that Janah was proposing was fresh—not so much a restraining of the capitalist model as a repurposing of it (and certainly not at the cost of environmental degradation; she was all for sustainability).

Simply put, it was this—if you are a socially-conscious business owner, particularly in a wealthy country, do not wait to do something good for the needy once you’ve hit all your goals. Engage them in some capacity, no matter how small, the moment you are able to employ workers.

Janah’s model was practical but it is not surprising that she had to make repeated attempts to persuade others to involve themselves in it. Philanthropy is, at the end of the day, still safer.

It is easier and more affordable for those with capital and influence to stick with it. Handing a poor person a fish to eat is easy. Teaching a man to fish is dangerous. If you employ the poor they might end up with useful skills, experience and ambition, and that can threaten and radically alter the existing power structures of the world… a scenario not everybody would want to see.

Despite the opposition, Janah remained positive. She saw that consumer habits were changing. The younger generation, especially, she insisted, was passionate about social issues. Nine out of 10 millennials were likely to switch brands to support an important mission, and they could distinguish between causes that were genuine and those that were fluff.

She was also heartened when she saw people who’d felt depressed and disempowered politically—with the rise of an extreme, intolerant populism—purchasing goods and services from vendors who addressed poverty. The shift in attitudes was gradual but it was real.

The final note

Social entrepreneurship was hard, and Leila Janah admitted. It would take an emotional toll on her. She kept herself sane by meditating, by contemplating the vastness of nature, by doing yoga, by kitesurfing. She derived a sense of joy from the many stories of “post-traumatic growth”—the opposite of PTSD—that she’d heard. Indeed, often people who had managed to reach the other side of excruciating suffering also ended up on a new ontological plane, with a more powerful view of existence, and that was good news.

Furthermore, she found strength in her own free will. We cannot always control what happens to us but we can choose our response, Janah said once, echoing Auschwitz survivor Viktor Frankl. That was liberating, a reason to always be hopeful.

Until her last days, Janah remained full of light, free of bitterness. She slowed down and became more attentive to the marvels of the world, massive or minute. Instead of participating in her usual adventure sports and salsa dancing, she took to painting and playing the ukulele. She spent quality time with friends and family, particularly cherishing the company of her supportive husband, Tassilo Festetics, whom she’d married just after her diagnosis in 2019.

She also began reflecting deeply on motherhood. She had had her eggs frozen a few years before but the cancer had rendered her incapable of carrying a child. She accepted that even if she survived the disease, she would never be a biological parent. Her feeling of physical lack and loss was mitigated by her having “birthed” two companies. It was a”crude analogy”, as she admitted, but it gave her some peace and satisfaction.

Ultimately, her life’s philosophy revolved around a quote from her grandmother Christiane, a Belgian who hitchhiked around the world before meeting her grandfather in Calcutta in 1948. “Don’t worry so much. Trust the world. It’s a vast, beautiful, wondrous place.”

It is easy to be cynical, to assume that everybody is out to get us, Janah pointed out, but somehow Christiane’s words made her persevere. “As I’ve gotten older,” she wrote, “I’ve interpreted that as, to find success and happiness, you have to take risks. Sometimes you have to step outside of what you know and get a little dirty.”

Her willingness to get dirty bore fruit. Just two months before Janah’s death, Samasource raised $14.8 million to scale up its operations. Her father, who was initially ambivalent about her quitting a promising career to start a social enterprise, mentioned to me recently that what she started had outlived her, and that’s how he knows she was on the right path.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

One Comment

Gwyneth Leser

Good article! We are linking to this great post on our website. Keep up the great writing.