Between the lines: is a non-feminist approach to Jane Austen possible?

The year is 2020, but chances are most people still associate Jane Austen with light-hearted, clichéd romance. The seemingly endless supply of cinema and TV adaptations of her novels, regarded worldwide as classic romantic comedies, plays an important role in this.

Given the enormous popularity of Pride and Prejudice, many enthusiasts will hear the name “Austen” and think of Colin Firth’s superbly played Mr Darcy, immediately remembering the famous scene where he emerges from a pond drenched and half-dressed in the 1995 BBC miniseries based on the novel.

On the other hand, both in academia and in the most recent adaptations of Jane Austen’s stories, there appears a marked trend to update the author’s social commentary to the perception of our own world as a very liberal one.

It’s as if Jane Austen sits uncomfortably at the edges of our perception. Her fictional world is either the stuff of shallow romance, not rebellious enough, or she’s altogether too radical and mysteriously subversive with every comma.

Some of the more recent spin-offs of Austen’s fictional world have “Lizzie” Bennet as a graduate student and young professional still living at her parents’ home, and Emma Woodhouse as a company-owning lifestyle coach and matchmaker (in The Lizzie Bennet Diaries and Emma Approved web-series respectively). Both shows feature Austen’s heroines as comically outspoken and tenacious – in a word, exaggerated 21st-century versions of the originals.

It’s a puzzling predicament that may confuse the reader faced with such a polarisation of interpretive approaches.

That Austen was a pioneer in many things is certain, but a line must be drawn between translating stories to a modern-day setting and overly stretching the fabric of her fiction for the sake of crowd-pleasing.

There’s more to Jane Austen than bonnets and bachelors – a whole lot more. Maybe not martial arts experts or zombie-slaying protagonists (as in the spin-off Pride and Prejudice and Zombies), but her heroines are exciting and revolutionary in many other ways.

One of the things that makes Austen such a great novelist is her unique portrayal of female characters as well-rounded individuals, whom we better relate to the more we get to know them. Who can help agreeing with Elizabeth Bennet’s honest sarcasm in one of her most memorable lines,

“I could easily forgive his pride if he had not mortified mine”?

The vast majority of sentimental novels (a popular genre in the 18th century) depicted women in unrealistic extremes of human behaviour: they were either paragons of virtue like Richardson’s Pamela, or the damnation of good-hearted men like the beautiful seductress Manon Lescaut. Going well against the grain, Jane Austen’s heroines were a three-dimensional wonder, embodying profoundly human contradictions. Elinor Dashwood is extremely rational and composed, yet capable of deep feeling. Fanny Price is thoroughly pure-hearted and very intelligent. The spoiled Emma Woodhouse is passionate about giving back through charity. And Lizzy Bennet is hopeful and cynical about the prospect of matrimony in equal measure.

Austen was one among several writers approaching the so-called ‘woman question’ during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Through fiction she exposed the daily trials women faced while fighting to have a say in their own lives a whole century before the suffragettes took over Victorian political debates defending women’s right to vote.

Since then, literary critics have interpreted Austen’s stance on gender politics in the most diverse ways. She was a parson’s daughter isolated from the cosmopolitan world, writing stories she could have heard from provincial gossip; a politically intelligent, conservative monarchist who endorsed her society’s mores; a radical Jacobin who would have England follow in the footsteps of the French towards a republican regime; an abolitionist; a staunch supporter of colonialism; a 21st-century feminist who lived before her time and lacked only the modern terminology we have coined in recent decades.

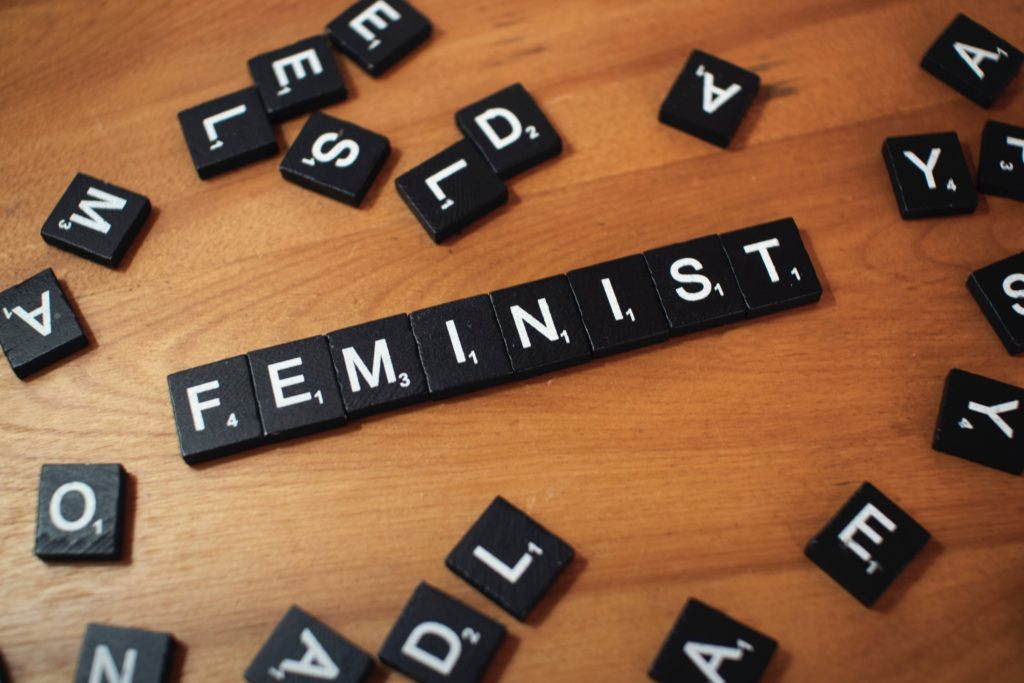

From the end of the 20th century onwards, the number of feminist interpretations of Austen’s novels continually rises with no apparent change in direction. Gone are the days when a scholar could regard Jane Austen as downright conservative, as Marilyn Butler does in her influential work Jane Austen and the War of Ideas, and meet the general approval of reading communities.

It begs the question, is a non-feminist approach to Jane Austen even possible at this stage?

Given her own textual strategies to shed light on contemporary women’s struggles, Jane Austen cannot be divorced from feminist readings and interventions in the 21st century – but this question goes beyond a simple ‘yes or no’ answer.

Jane Austen has been painted a million different colours over the two centuries since her early death in 1817. You can tell as much by taking a handful of well-known films: When Harry Met Sally, You’ve Got Mail, Pretty Woman, not to mention the more recent (and more obvious) examples of Bridget Jones’s Diary, Bride and Prejudice, and the earlier mentioned Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Despite their various settings and stereotypical dressing in ‘Rom-Com’ costumes, all these films are cited by English professor Deborah Cartmell as borrowings from Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

Perhaps this insistence on tagging Austen as the mother of modern romantic comedy explains why most interpretations and adaptations of her novels from the last 20 years follow the opposite trend. They radically update the original stories, modifying the characters to make them fit in with our cultural landscape as much as the parameters of plausibility can bear.

A striking example of this is the 1999 film adaptation of Mansfield Park. Director Patricia Rozema gives a makeover to the demure Fanny Price, who cannot stand up for herself for approximately 95% of the plot in Austen’s original novel. In the film, Fanny is far more sharp-tongued. Emboldened by her moral convictions, she resists her uncle’s attempts to coerce her into an unwanted marriage with scoundrel-in-disguise Henry Crawford more boldly than Austen’s heroine ever could. “I’ll not be sold off like one of your father’s slaves”, she tells her beloved cousin Edmund.

The film incarnation of Fanny even references the polemical 1807 Slave Trade Act, whereas the original character asks her uncle about his slaves without demonstrating much knowledge on the topic, receiving “dead silence” in response. Mansfield Park is one of the less popular of Austen’s novels precisely because of its graver and more timid heroine. Yet, using brazen language sure to make Austen bristle, film-Fanny chastises Mansfield’s patriarch unflinchingly.

“Correct me if I am in error”, she says, “but I’ve read that if you were to bring one of the slaves back to England there would be some argument as to whether or not they should be freed.”

It certainly would be nice to believe Jane Austen was as passionate about abolitionism as she was about women’s autonomy within the paternal home and in marriage. Her views on the matter were never fully disclosed, though.

But there is a genuine element in Austen’s feminist agenda which often gets picked up in modern retellings: her consistent defence of women’s right to choose their partners in marriage, and to condemn anyone who has wronged them. Against a cultural notion that women should always keep a gracious, pleasant, and uncritical poise, Austen’s heroines won the hearts of readers throughout the centuries for their inner strength and truthfulness.

If even the original Fanny Price could shyly state,

“I cannot think well of a man who sports with any woman’s feelings”,

how much greater an impact did Emma Woodhouse’s unabashed egocentrism have when she remarks,

“I always deserve the best treatment, because I never put up with any other”.

Elizabeth Bennet’s refusal to marry someone who could never make her happy inspired generations of women, as she confidently asserted her independence of mind:

“You must give me leave to judge for myself, and pay me the compliment of believing what I say”.

Strong-willed and morally authoritative female characters were not unprecedented in Jane Austen’s day. But this novelist has the merit of having drawn heroines more popular and more widely loved than any of her contemporaries – and, arguably, than any author who came after her.

In keeping with her exposure of women’s difficulties in a society which denied them autonomy, Austen’s most famous works are initially motivated by the economic struggle of unprotected women. The plots of both Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice are kick-started by the unfair reality surrounding the Bennet and the Dashwood families, who depend on male relatives to keep a roof over their heads.

It was a truth universally acknowledged that, according to 18th-century law, none of these women could inherit money or land after their fathers’ death. Mrs Bennet’s obsession with securing her daughters’ future by marrying them to wealthy suitors surely makes a lot more sense now, as does Elinor Dashwood’s emotional sacrifice in assuming the position of the sole pragmatic figure while her widowed mother and her sisters face impending destitution.

Jane Austen’s female-centric tales reflect in vivid detail some of the greatest struggles women faced in her society. It is only fitting that modern retellings adjust the plot circumstances to convey a similar sense of social inequality surrounding the heroine.

To name only a few, the wage gap and the unequal division of household responsibilities are sufficient evidence that any modern-day Austen heroine would be plagued by issues not too far from those in the pages of her novels. But caution must be exercised when adding too much contemporary substance to the stories, lest the loyal Austen enthusiast becomes as indignant as Lady Catherine de Bourgh: “Heaven and earth – of what were you thinking?”

One Comment

Mary Flannery

I think Jane Austen would be dismayed at some of the directions her characters have taken in several well-known adaptations. Recently, a person said to me rather snootily, ‘But Jane would have moved with the times.’ But what are our Times, and are they anything to admire anyway?

I read Austen to get back to a more highly-principled era, where Duty was very important, and where God was in everybody’s life, and where going to Church on Sundays was normal, where promiscuity, drug-taking and abortion were not normalised as they seem to be now. Yes, these things existed, but people knew they were wrong and children grew up knowing that.

God was a very important part of Jane Austen’s life.

Many of her readers have trouble with the fact that Austen was a committed Christian, went to church twice on Sundays and wrote prayers for her father to preach from. She had her faults as a person too, as all Christians do. But she lived and died a Christian. Attempts to make her over into a ‘woke’ 21st century feminist mystify me. But that’s just me.

She just might hold conservative views. She might be capitalist, She might be prolife (and feminist too). She might be a monarchist. She might have voted for Brexit. We don’t know and is it really relevant? She’s been dead a long, long time.