The race to save the planet: can we still win?

To save the planet and save lives even the shock drop in emissions caused by the pandemic is not enough. We need a new world economic order, argues Margareth Sembiring.

Silver linings are hard to find in the global black cloud that is COVID 19, but one might just be the fact that the lockdown could possibly reduce this year’s carbon emissions by up to seven per cent.

The Paris Agreement’s central aim was to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to one and a half degrees Celsius. Up to the pandemic, there had been little success in meeting this target.

But by slowing down the world’s economy so drastically, COVID has achieved what governmental activity had thus far failed to do. The COVID-linked change is close to the ideal 7.6 per cent drop that the world needs to commit to every year between now and 2030 to reach the Paris target.

Two observations strike me. First, the sheer scale of changes to economic activity that is needed to save the planet which the current decarbonising and greening approaches are struggling to achieve. Second, the need for a serious, conscious decision to make deep changes, and the requirement for imaginative and effective policies to prevent massive unemployment and increased poverty that will result from unplanned disruptions to economic activities.

Decarbonising and greening: the challenges

Until now decarbonising and greening have been among the most dominant strategies to address climate and environmental issues. They essentially entail a process of substitution. Solar and wind energy replace coal plants, electric transport replaces conventional vehicles, more efficient lighting and buildings replace older models, biodegradable replaces plastic, and so the list goes on ….

Despite the availability of environmentally friendly alternatives, decarbonising and greening efforts are progressing slowly and results have been modest at best.

The most striking evidence of this relative failure is the two per cent rise in carbon emissions in 2018, which was the fastest in seven years, despite renewable sources’ increasing share in global energy consumption. The growing emissions were the result of expanding energy consumption that nearly doubled the 10-year average.

In other words, at the global level, renewable sources act more like an additional source of energy instead of a fossil fuel replacement, to feed the increasingly energy-hungry world.

The phenomenon is hardly surprising. Isolating carbon emissions from overall economic growth efforts hampers governments and businesses from making meaningful low-carbon transitions.

Considering the growth imperative, governments need to consider which sectors to tax and which to subsidise, ensure just transition, and decide on infrastructure investments while balancing the pleas from competing voices in the domestic setting.

The costs of solar and wind powers have gone down significantly in the last decade, and green businesses are justifying their value by emphasising job creation and their positive contribution to the economy while saving the planet at the same time. But until governments are confident that low-carbon alternatives do not jeopardise, or indeed can be more beneficial for, growth-related interests, decarbonising and greening will generally remain ineffective motors of change.

Businesses are likely to embrace more sustainable alternatives if doing so gives them more benefits, or at least does not hurt their profitability. They are therefore awaiting reliable policies that will minimise investment risks, metrics that can measure environmental, social, and governance objectives in financial terms clearly, and investment returns and executive salary that are linked to environmental and societal benefits, before they can be certain about really greening their operations. It is of little surprise, therefore, that in 2018 less than 7,000 companies of the millions worldwide declared their emissions, and only one in eight managed to decrease their annual emissions every year. Greening businesses has a long way to go.

The narrowing time window necessitates more urgent and bolder measures that go beyond just decarbonising and greening.

The high-carbon element is just a part of the larger demand-driven economy made up mainly of natural resource extraction, production, consumption, and waste generation. As a reduction in economic activities brings down with it the emission levels as evidenced in the current COVID-19 situation, the focus needs to focus from high-carbon to production-consumption activities.

The link between increasing consumption and environmental stresses is well recognised. Every year since the 1970s, the world’s consumption has been exacting a hefty toll on the Earth’s resources – more than it can regenerate.

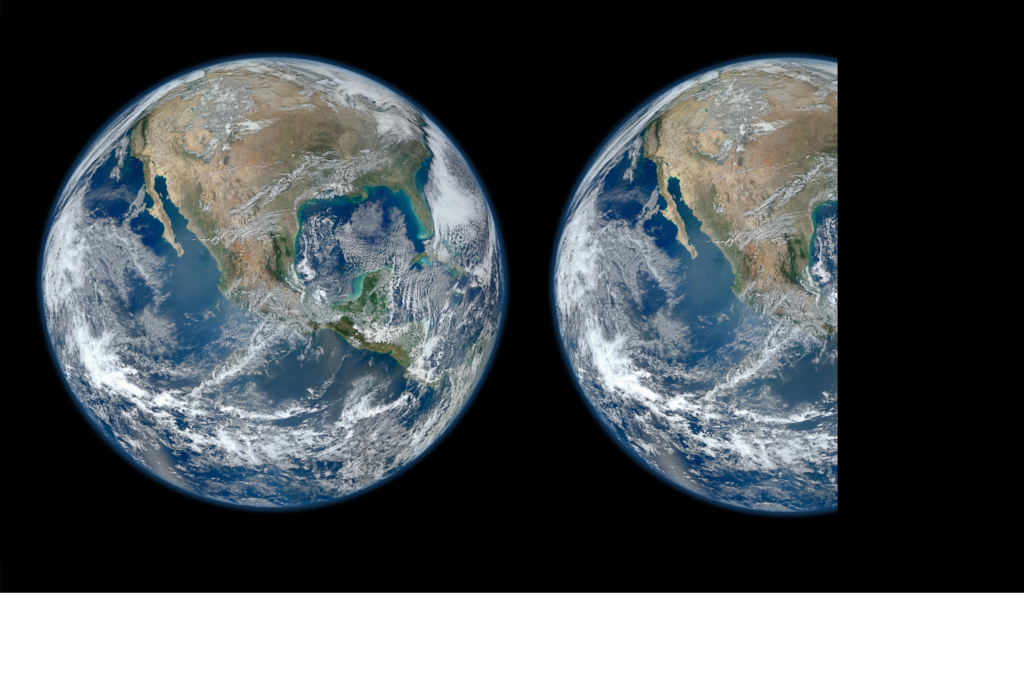

Humans use ecological resources as if we lived on 1.6 Earths with advanced economies, and by extension the richer segments of society, disproportionately consuming more.

Before Covid this figure was actually 1.75.

In 2016, consumption in North America and Western Europe needed 4.95 and 2.98 Earths respectively, whereas Asia and Africa needed 1.46 and 0.83 Earths respectively. Natural resource depletion driven by high consumption is consistent with 2.3 million km2 of forest being deforested globally between 2000 and 2012 with only about 35 percent being reforested.

The devastating impact of this gross over-consumption on nature poses direct human security challenges especially for the poor. About 80 percent of the world’s poor live in rural areas where the harvesting of natural resources makes up 50 to 90 percent of their livelihoods. Natural resources are the natural capital of the poor. The COVID-19 pandemic has confirmed that the poor are among the least able to cope during crises. While strengthening social protection measures and other anti-poverty policies is undoubtedly desirable, the vicious cycle can only be broken by tackling the problem at its source.

Nature takes time to heal. A forest on average undergoes about a two per cent recovery per year. Contrary to popular belief, human efforts do not help the ecosystem restore itself significantly since ecological recovery is best left to nature itself.

Reducing consumption is therefore critical not only to bring down emissions, but also to give nature the time and space it needs to recover from extraction damages, and to give back to the poor their dignity and the resilience they need in times of trial through sustainable livelihoods.

Towards a new model of development

The current economic hardship caused by abrupt COVID-19 interventions forces governments to think of ways to save jobs and businesses, particularly small and medium enterprises, and to re-employ those who have lost their livelihoods, and thus alleviate poverty. While this is certainly desirable, the pandemic experience has provided some points for reflection which suggest that recovery measures need to consider other factors beyond the economy to avert future climate-induced disasters.

The economic miracles post-World War II and post-Great Depression undoubtedly present a hopeful picture for a post-COVID-19 world. There is a need to be mindful, however, that those eras operated neither on massive overdemand of resources – so called overshoot – nor had they transgressed interconnected planetary boundaries within which the Earth can function safely as we are doing today.

A post-COVID-19 green economic recovery that involves a sweeping investment switch to low-carbon alternatives across multiple sectors including energy and electricity, land-based transport, industry, and buildings, may be compatible with the Paris target by the year 2030. But given the lack of ambitious climate actions so far, it remains to be seen whether the current global pandemic can provide the impetus needed for a meaningful green recovery.

A bold determination to switch to a just and equitable Earth-centred economic paradigm is needed, and a consensus among people, governments and businesses is required to effect a change in the high consumption lifestyle. In comparison to today’s consumption-driven economic model, this may entail low, no, or declining growth. This does not necessarily lead to increased unemployment, poverty and inequality, however, as studies have shown that with well-calibrated policies, progress without growth is possible.

Given the fast-closing time window for emission reduction, attempts at decreasing resource demand relative to the previous levels through greener products, increased efficiency, a circular economy, net-zero, and sustainable resource management may help, but will probably not be sufficient. Given the reality of our ecological deficit and the accompanying plight of the poor, a fundamental rethink is needed – a well-designed economic model aimed at an absolute reduction in consumption to reach an ecological balance is imperative.

Post-COVID-19 recovery will play a critical role in saving Mother Earth, the poor, and humanity from climate disasters. The alternative does not bear thinking about …

This is a slightly enlarged and edited version of an article which first appeared in the NTS-Asia newsletter of August 2020: https://rsis-ntsasia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/NTS-asia-newsletter-August2020.pdf

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!