A Government response adrift

The treatment of asylum seekers and refugees needs our urgent attention, argues Brian Clarke.

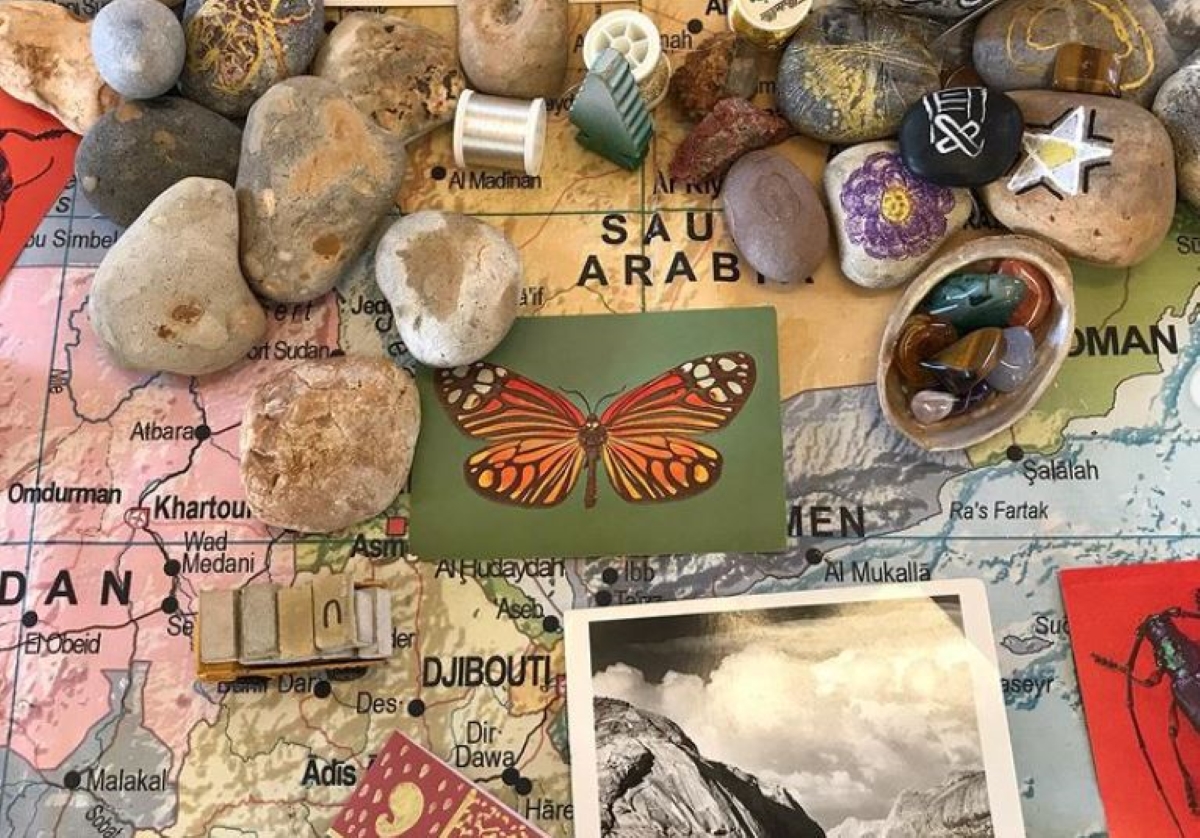

All images of artwork displayed in this article are kindly provided by Art Refuge charity. Art Refuge uses art and art therapy to support the mental health and well-being of people displaced due to conflict, persecution and poverty, both in the UK and internationally. Thanks to Brian for his request to showcase refugees’ art.

Known only to family and friends during his life, but known to the world for the circumstances of his tragic death, he is one of the few that we know by name. Found at the water’s edge near the Turkish resort of Bodrum lay the washed-up frame of a lifeless three-year-old in his red T-shirt and navy blue trousers. Lying face down, head in the sand, the water lapping up to his hair – Alan Kurdi became an icon of suffering.

That was five years ago…

The drowning of Alan, his mother Rihan and brother Galip was the tragedy of just one family. But it’s a fate not unknown to many other families, each with their own unique stories.

In the days after Alan’s death the world expressed its shock, demanding that things should change. But more than five years on, how much has really changed? The spotlight which his death caused to shine briefly on the suffering of those displaced by violence, war and persecution has grown dim but it’s a reality that continues to destroy lives on an inhuman scale.

The numbers dying in the Mediterranean are significantly lower than they were five years ago, but the fact it’s still happening at all is a stain on the world’s conscience.

Amnesty International records that there are 26 million refugees globally: half of them are children and 85% of them are being hosted in developing countries.

What this reveals is that for all the shock displayed in the West, the powerful and wealthy members of the international community have failed to take their meaningful share of responsibility. The picture of Alan elicited some immediate action among the politically influential, and offered an emotional kickstart to wider public discussion in the tabloid press, but regrettably it has yet to secure the long-lasting change which some had hoped that it might bring.

Instead, debate on the issue has become muddled, polarised and at times lacking in basic humanity. As the poet Warsan Shire eloquently put it:

“no one leaves home unless

home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as well –

you have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land.”

The politics of international obligations, how far they extend and what they should look like in practice in terms of creating a coordinated response, seem remote from the human tragedy that happened in the early hours of that September morning in 2015. For all the talk of ‘never again’, it’s a tragedy which has happened again and again again and again … One looks to governments around the world and wonders whether empathy has a place in modern international politics.

Looking at my own country, the British government has its own questions to answer over its past and future policy decisions. It recently floated plans which include processing asylum seekers in detention centres offshore and the deployment of artificial wave machines to keep refugees at sea, unable to land. Neither, can the public be confident that those already in the UK and seeking asylum are being treated with dignity. Those detained at camps in England (such as Napier and Penally) have been housed in cramped conditions despite an outbreak of Covid-19.

Alarmingly, a freedom of information request revealed that in 2020 more people died in Home Office asylum accommodation than lost their lives in crossing the Channel.

As many as 29 people died in home office accommodation, five times as many as died in attempting to cross the Channel over the same period.

Of similar concern are proposals set out in Britain’s New Plan for Immigration which seek to penalise asylum seekers based upon their route of entry into the UK – a proposal which some warn risks breaching international law and the UK’s obligations under the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Such plans appear to be in tension with Article 31 of the 1951 Refugee Convention, which explicitly states: “Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence, on refugees (…) coming directly from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened.”

Moreover, it is worth highlighting that UK case law contains a precedent which stipulates that asylum seekers do not have to claim asylum in the first country they pass through, and that ‘some element of choice is indeed open to refugees as to where they may properly claim asylum’.

“We drove twice to the tented area where people are living to try to fathom the reconfiguration of the current living conditions for ourselves. We were shocked by the new fenced off areas into which people seem to be penned in, or perhaps it was to keep them out?”

The pernicious narrative that those seeking asylum are commonly ‘making unmeritorious claims’ overlooks the fact that more than a third of people are granted refugee status on appeal in the UK – meaning one in three people who appeal their decision were initially rejected unfairly.

The importance of this cannot be overstated when one observes that the proposed powers to deport asylum seekers before their claims have even been processed deny them not only the equity and fair process they are entitled to, but risks jeopardising their very physical and mental wellbeing.

Sometimes it’s useful to put a problem in context, and here numbers can help …

There are currently fewer than 140,000 refugees in the UK, equivalent to 0.26% of the country’s population.

By contrast, Lebanon, a developing country with a vastly weaker economy, is host to over 1.5 million refugees, making up 21.8% of the population.

However, the UK government has plans to cut its foreign aid allocation to Lebanon by 88%. For a country that ranks in the top 10 largest economies in the world this seems like an abdication of its responsibility not only to invest in regional havens but also to provide a safe place of refuge.

In a Christmas message delivered in 2015, Alan’s father, Abdullah Kurdi, said: “If a person shuts a door in someone’s face, this is very difficult. When a door is opened, they no longer feel humiliated. At this time of year, I would like to ask you all to think about the pain of fathers, mothers and children who are seeking peace and security. We ask just for a little bit of sympathy from you. Hopefully next year the war will end in Syria and peace will reign all over the world.”

One reads these words more than five years on with a sense of angst, for so little has changed when so much change is needed.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!