Honouring the world’s desaparecidos

Mary Aileen Diez-Bacalso describes her lifework campaigning for ‘desaparecidos’, people who have been forcibly taken and ‘disappeared’ by those in power, and supporting their families.

This is an excerpt from a heart-wrenching poem written by the wife of a desaparecido, one of those many people who have ‘disappeared’, involuntarily imprisoned or, frequently, killed by State authorities.

“As dawn breaks every morn, my heart awakens with renewed yearning

Yearning for your return

As dawn breaks every morn, my pain for your loss deepens

My fears for your safety and well-being heighten

Not knowing where you are, not knowing what you have to endure

The yearning, the pain, the fears, the uncertainty

Grow ever more with each passing day and each passing year

As dawn breaks every morn…”

The poem was recited at a press conference in Thailand organised by Protection International, Justice for Peace Foundation and FORUM-ASIA on 30 August, for the United Nations International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearance, which is now observed annually on that date.

Only a family member of a victim of enforced disappearance could compose a poem that comes so truly from the heart. It was written by Shui Meng Ng, the wife of development worker Sombath Somphone who was forcibly taken in front of the Vientiane police station in Laos on 15 December 2012.

Shui Meng is one of the millions of family members around the world of the disappeared who, from pillar to post, continue to search for their loved ones. Over the past 12 years, she has tirelessly lobbied at every national authority in Laos and in many other countries. She has visited various foreign embassies and spoken at the United Nations in her quest to uncover the truth about Sombath’s disappearance.

But like many other family members of the disappeared, she has tragically been unable to find the answer to her most haunting question: “Where are you?”

During the event, four other family members from Thailand were present, who also paid tribute to their disappeared loved ones by singing songs, and offering flowers and prayers. They delivered a symbolic letter stamped with photos of disappeared people to be posted to the office of the new Thai Prime Minister, Paetongtarn Shinawatra, as a reminder of their ongoing search for truth and justice.

Despite the passage of a domestic law against torture and enforced disappearances in Thailand in August 2022, the family members recounted that, due to the law’s non-retroactivity, they must present new evidence for their cases to be reopened. And this even after Thailand ratified the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (ICPPED) in May 2024, which explicitly states that enforced disappearance is a continuing crime. Yet the whereabouts of the victims remains unknown, and their family members continue to suffer from the consequences of the crime.

The event was followed by a diplomatic briefing, hosted by the Royal Netherlands Embassy in Thailand and attended by representatives from foreign embassies, civil society organisations, and the UN office in Thailand. In the briefing, a film on the 20-year enforced disappearance of a Thai lawyer, Somchai Neelaphaijit, was screened, and his wife, Angkhana Neelaphaijit, now a senator, spoke about the imperative of never giving up the search until truth is revealed and justice is served.

Simultaneous with the Thai commemoration, many organisations around the world held activities to honour the victims of enforced disappearances. These activities included memorials, prayers, candle lighting, rallies, film showing, concerts and poetry reading, all aimed at creatively paying homage to the world’s desaparecidos whose memories must never be forgotten by concerned families and society at large.

Background

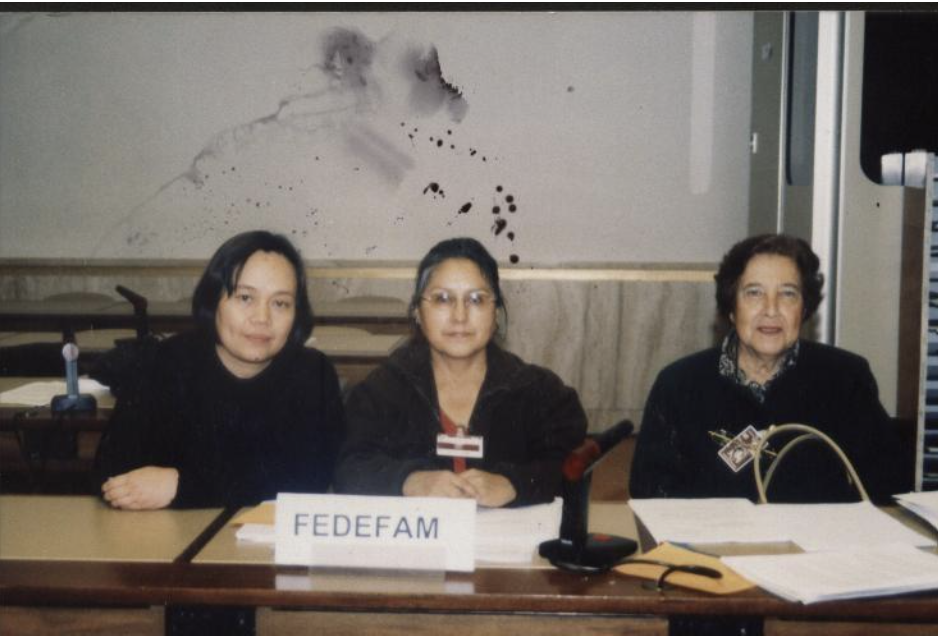

The International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances was first commemorated as a result of the initiative of the Latin American Federation of Associations of Relatives of Disappeared-Detainees (FEDEFAM), during its first Congress in San Jose, Costa Rica in 1981. As enforced disappearances grew to a global scale, it was later adopted by several associations of families of the disappeared across continents.

After decades of knocking at United Nations’ doors, the organisation gave it official recognition in 2011 This international recognition is among the invaluable gains of the struggle of families of desaparecidos for truth and justice with the solidarity of civil society organisations.

Also noteworthy is the adoption of the ICCPED by the UN General Assembly on 23 December 2010, which has, to date, been ratified by 76 states.

However, in comparison to other core international human rights treaties, it is far from achieving universal ratification and implementation.

The number of ratifications and the extent of implementation pale in comparison with the ever-increasing cases of enforced disappearances occurring with each passing day.

Personal involvement

In my more than three decades of work on enforced disappearances in the Philippines, other Asian countries, and beyond, I have had the honour and privilege of meeting hundreds of family members of the disappeared across more than fifty countries. I have found myself immersed in their struggles in my own country, the Philippines, in Indonesia, Thailand, Timor-Leste, in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and in the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir.

I have also visited distant nations such as Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Mexico, Guatemala, and El Salvador; in Africa, Benin, Kenya and South Africa; and also Croatia, Poland and the USA. Family members of the disappeared are in every nook and cranny of the world.

They speak and share the common language of sorrow, fear and uncertainty and of the undying hope against hope that one day they will see their loved ones again. They display photo albums, cherished memorabilia, literary pieces, and artworks created by the desaparecidos, reminding us of the lives and legacies these left behind. Clinging to the slimmest of hopes for their loved ones to come back, family members of the disappeared gave me documents with an appeal for help in their endless search.

A sense of secondary trauma enveloped me, yet I felt enriched by their resilience and hope — a hope that persists despite every reason to despair. This enduring hope has inspired me to continue my journey alongside them on the path less trodden, through the long and arduous road to truth and justice. The years of struggle together are unforgettable, marked by countless activities we shared, including:

- Visits to their homes where I had the opportunity to receive their warm hospitality despite their material poverty;

- Exhumation missions in remote areas, where I witnessed the poignant reactions of families confronting the end of a seemingly endless search. The mix of relief and pain was palpable as they received definitive answers about their uncertain losses, particularly when remains were positively identified;

- Meetings with government agencies and heads of states which always ended with promises of collaboration and support but, more often than not, did not produce concrete results;

- Memorials at monuments where the names of the desaparecidos are engraved. Family members gathered to offer flowers and light candles in honour of their beloved lost

- Lobbying activities at seats of governments and at the UN for the adoption of the ICPPED;

- Marches and rallies where we linked arms to demand the enactment of domestic laws against enforced disappearances and the ratification and implementation of the ICPPED;

- Reunification of stolen children from Timor-Leste with their biological families. The children had been taken to Indonesia by soldiers during the Indonesian occupation;

- Psycho-social accompaniment for families of the disappeared to recognise their intrinsic strength and help them go beyond the devastating effects of enforced disappearance.

For family members of desaparecidos, the journey to truth and justice is long and arduous.

It entails courage, patience and persistence. It’s important to recognize both small and significant victories which empower families to confront powerful perpetrators and persevere in this difficult crusade and quest for justice.

Marta Ocampo de Vasquez

One of the many family members of the disappeared who made a significant impact on me was the late Sra. Marta Ocampo de Vasquez, then president of the world-renowned Madres de Plaza de Mayo.

These indomitable women are mothers of those who were victims of enforced disappearances during the Argentinian dictatorship in the 1970s. Every Thursday afternoon, they march around Plaza de Mayo, the square in front of Casa Rosada, which is the seat of the Argentinian government to chant “Alive, they were taken from us. Alive, they must be returned to us.” Till now, the few remaining mothers who are still alive continue the weekly marches.

I was fortunate to be with Marta during the three-year drafting and negotiation process of the ICPPED at the UN in Geneva and in many congresses of the Latin American Federation of Associations of Relatives of Disappeared-Detainees (FEDEFAM).

Thanks especially to her untiring efforts, the treaty was eventually adopted by the UN General Assembly on 23 December 2006. A couple of months later came the historic signing of the Convention in the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs by 57 states on 6 February 2007. The treaty entered into force in December 2010.

Before returning to her country, in a very memorable moment, Marta, in her eighties, told me that she had accomplished her mission.

Acknowledging that she had only a few years left, she asked me to continue the work for the disappeared and their families.

That was one of the most poignant moments I have ever experienced, being a part of the movement envisioned to erase enforced disappearances from the face of the earth.

For one last time, I visited Marta in her home in Buenos Aires in December 2013, shortly after I had received the Emilio F. Mignone International Prize for Human Rights. In her living room hung a photograph of a young woman in her twenties. When I asked about it, Marta simply looked at me, her gaze heavy with unspoken sorrow. I later learned this was a picture of her daughter, Maria Marta, who disappeared in 1977. The perpetrator, Schilingo, had confessed that she was one of the victims of the ‘death flights’, discarded into the ocean, never to be found.

Little did I know that it was my last meeting with Marta, a remarkable woman, whose lifetime struggle to find her disappeared daughter contributed, in no small measure, to the global fight against enforced disappearances.

The fight continues

In its July 2024 report, the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (UN WGEID), stated: “since its inception in 1980, the Working Group has transmitted a total of 61,626 cases to 115 States. The number of cases under active consideration that have not yet been clarified, closed or discontinued stands at 48,619 in a total of 100 States. During the reporting period, 199 cases were clarified.”

Taking into account the reality of underreporting due to factors such as families’ lack of access to authorities, fear of reprisals, displacements due to militarisation and many other, the official statistics from the UN WGEID do not reflect the actual number of cases, especially in countries where organisations of families of the disappeared do not exist.

This alarming phenomenon has prompted civil society organisations and states, through the initiative of the Convention Against Enforced Disappearances Initiative (CEDI), to organise the upcoming First World Congress on Enforced Disappearances to be held in Geneva on 15-16 January 2025. This Congress is being held in response to official resolutions from both the UN Human Rights Council and the UN General Assembly.

First World Congress

The primary objective of this inaugural gathering of families of victims and state representatives is to promote the universal ratification and implementation of the ICPPED. Through the lens of the victims, the congress seeks to address the heinous crime of enforced disappearances with concrete actions and tangible outcomes.

Equally important is to echo and share the congress results with organisations of families of the disappeared on the ground, which, along with other civil society organisations, serve as the backbone of the difficult journey of attaining the much-cherished dream for a world without desaparecidos.

Fulfilling the objectives of this congress at the grassroots level will serve as a very profound and meaningful tribute to all the world’s desaparecidos.

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Mary Aileen Diez-Bacalso

Mary Aileen Diez-Bacalso is the Executive Director of FORUM-ASIA, a network of 87 human rights organisations from 23 Asian countries. Its headquarters is in Bangkok, with offices in Jakarta, Kathmandu, and Geneva. Having consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council and the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights, it works on issues of fundamental freedoms, civic space, human rights, sustainable development and climate change.