The art of connection: navigating friendship in the 21st century

Anthony Stratford draws on ancient wisdom to re-discover how we can form true friendships at a time when it seems ever more difficult to do so.

Later this month we celebrate International Friendship Day. Never heard of it? That probably says a lot about the state of friendship in our society and time.

Any form of commemorative day either celebrates a clear event in the past, recalled to keep its memory and lessons alive, or an aspiration to achieve. The 30th July occasion is clearly in the latter category. 21st century man – and woman – is struggling to make friends.

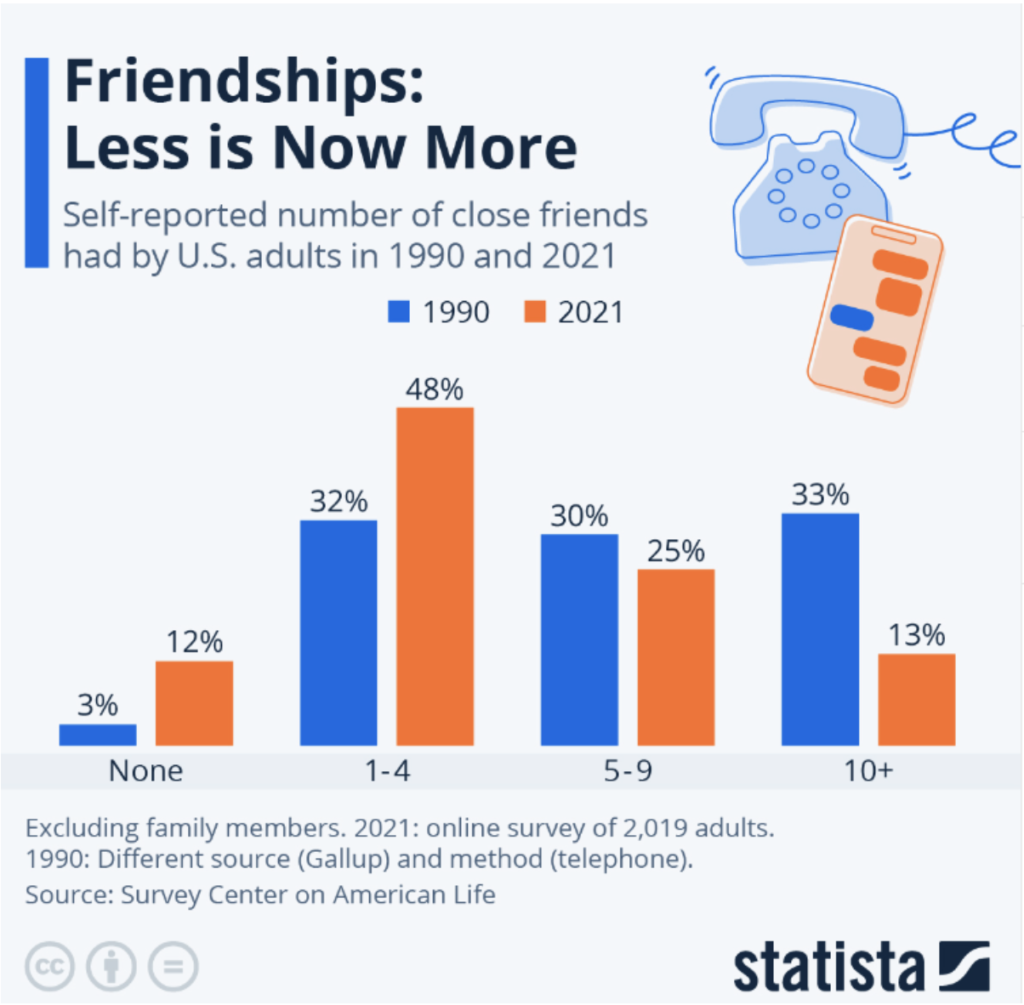

A 2021 survey by the Survey Center of American Life revealed that 12% of people claimed they had no close friends – a fourfold increase from 30 years ago. To me, that’s a serious issue.

But maybe the problem is we don’t even know what a friend really is. Because it may not be evident. To help us to do so we could do far worse than go back a few millennia to explore the wisdom of the great Greek philosopher Aristotle who wrote in detail about this topic.

Writing in the fourth century BC, Aristotle dedicates two books in his Ēthika Nikomacheia (Nicomachean Ethics) to friendship, whereas for every other topic he dedicated only one book to each – a clear sign of how much this issue mattered to him.

The Ethics is dedicated to how to live a good life and for Aristotle there is no happiness without friends.

His work has an ascending structure: it takes us up to what really makes the happy man. It begins with the virtues, considers self-control and bodily pleasure, and then moves onto friendship as the penultimate good, with the ultimate one being the contemplation of God.

In other words, we can’t be truly good alone, and we can’t know God alone. Man is a political (social) animal and hence our wellbeing stems from common life, and that is something shared, not selfish.

Aristotle is very good at defining what for us is basic and intuitive, that is something we just assume, without knowing its definition. For example, we know what a friend is, and probably know what a good friend is, but how does one express that?

Aristotle simply defines friendship as ‘willing the good for another’. You could argue that you wish good for everyone, but that wouldn’t explain why you have so few friends. For Aristotle there is willing and willing. In other words, one thing is a vague desire for someone’s well-being. Another thing is really to want it and to take specific steps to bring it about.

There has to be a reason why you are friends with someone. But are you really a friend? Might it not be instead a comrade, a colleague, an associate, a benefactor, or an acquaintance? The differences are subtle but significant.

Everyone in that list is in some way a ‘friend’, but we all know that there are fake friends and true ones. Friendship can be more or less self-interested. This is not always bad but at least we have to recognise it to know to what extent the friendship is genuine.

What are fake friends? Aristotle doesn’t describe fake friends as those who talk badly of you behind your back. Those wouldn’t be friends at all. Instead, he describes a hierarchy of friendship as being based on the three objects of love: the useful, the pleasant and the good.

Friendship based on utility is when those “who love each other do not do so for the other in him or herself but for the sake of some good which they might get from them”. In other words, both parties seek to gain from the relationship.

“Those who love for the sake of utility love for the sake of what is good for themselves.” For example, a university colleague whom you ‘get on well with’ simply because you help each other with study. Once the exams are over, you cease to look for each other’s company.

Next are “those who love for the sake of pleasure. It is not for their character that men love ready-witted people, but because they find them pleasant”.

These are the friends you have a good laugh with because they think the same as you do, have a similar sense of humour, and essentially provide for a great time.

In short, “those who love for the sake of pleasure do so for the sake of what is pleasant to themselves.” This friendship is more widely sought after since it makes us ‘feel’ good. The friendship is there, as long as there is a party, but after that pleasure has been satisfied, the union might easily decline.

Notice how Aristotle does not say that friendships of utility or pleasure are necessarily bad. They aren’t and they happen all the time. The only difference is that there is a type of friendship which is even better.

The highest tier of friendship is that based on virtue.

“Perfect friendship is the friendship of people who are good and alike in virtue, for these wish well to each other by genuinely seeking the other’s good, and they are good themselves.”

Good in the aristotelian sense can mean two things. It can be virtuous (the right way to live) and so a means. Or it can be ‘the good’ as an end (the right goal to aim at), that is, human flourishing.

Many of us probably live out the first two categories of friendship, but the final category is harder to find. How can I make true friends?

Aristotle has another definition up his sleeve, one that I prefer: “a friend is another self.”

Look at your relationships. Can you honestly see a friend of yours whom you treat as yourself? Do you love your neighbour as yourself? This sounds very religious, specifically Christian, but in this case Aristotle had got there first. Is their sorrow your sorrow, their joy your joy? Perhaps that is where your problem lies. To see a friend flourishing is to flourish ourselves.

Friendship has to be based on virtue. Virtue to our modern ears sounds a bit odd, it smells Victorian, and so outdated and dull. But virtue simply means a good habit.

Aristotle defines virtue as a disposition, induced by our habits, to have appropriate feelings to achieve a certain end. By doing good acts, the habit becomes ingrained in us, part of us. Frequent generous deeds, for example, lead us to incline towards generosity. It becomes something we naturally do. Virtue is hence something good and desirable.

Obviously you can have ordered and disordered desires, such is life. We can love things that don’t help us, like someone whose company we enjoy but who brings us down.

Those who are alike are naturally attracted to each other. As the saying goes, birds of a feather flock together. So if we attract many ‘bad’ people, perhaps the problem isn’t them. Maybe we’re to blame.

Friendships have to be equal, one cannot just give and the other just receive.

Both parties invest, and both parties gain.

Some say that opposites attract, but there has to be some common ground whereby a friendship can begin to take shape. Friendships must therefore be equal. You can’t play a duet between a grade 8 pianist and a grade 1 cellist, both would struggle to aim at the level of the other. A king and a peasant would therefore struggle to be friends.

That said, there does seem to be some virtue in the fact that people can change. Being different doesn’t automatically discard a friendship, since there is virtue in the fact that people from different backgrounds can get along, but they have to align in their views and their ways of showing affection and they have to be open to the affection of the other. If not, friendship cannot be genuine.

So Aristotle is being a realist. A friend can and should help you be better, but the two of you need to have something in common for the friendship to flourish.

What factors in the modern world are hindering the formation of friendships in a way that Aristotle might not have foreseen? Socially speaking, we’re more connected than ever. Or are we?

Modern society makes us both ever more connected and ever more detached from each other. For all the good sides of technology, electronic disconnection is necessary for true human connection.

Modern problems require modern solutions. And the problem seems to be the deficit of proximity and quality time.

By living life in the fast lane, we aren’t taking the time required to form real friendship.

Aristotle talks about proximity and time being necessary for friendship. Liking someone’s story on Instagram is very different from walking together five kilometres to the nearest town.

Aristotle speaks of the importance of conversation which only deepens the friendship of virtuous people. They become better by working and living together, and are inspired and delighted by the other’s good qualities. Perfect friends don’t enjoy themselves by virtue of the activity they’re sharing, but the mere fact of being with each other.

Just spending time together doing apparently ‘nothing’ might be a first step. No video games, no phone, no social media. Walk with each other in the forest, chat without a time limit.

If I were to leave my house in search of new friends, where would I find them? Anywhere, but more likely, they’re already around you, so maybe we just need to go deeper with them.

Aristotle speaks of goodwill as a necessary first step in forming a friendship. Whether a friendship happens subsequently or not is a different matter, but goodwill is a necessary beginning. We actually have to foster a positive attitude towards others, and seek and see the good in them. In that sense, friendship is not always as spontaneous as we might think. It does need a bit of working on.

Goodwill, however, can only take us so far. Being nice is great, yet one needs to connect. But how? Typically, by common interests, or having something interesting to say. By being selfless, for example, and not checking your phone when meeting someone new which tells them they are worth being the centre of your attention.

One doesn’t need to be an extrovert, but for many extroverts this initial energy in meeting people can allow them to make many acquaintances, but they may not go so deep.

So friendship also requires an effort to grow in personal depth of character and even of interests.

A friend, that other self, is a soul you can open up to. You become one soul as you pour out your love into each other.

What is love? Unfortunately for us, love is a vague term that doesn’t mean much. But love in Aristotle’s time had four different classifications: storge, philios, eros and agape.

While love regarding friendship refers to philios, agape is the highest love. Philia expresses the love of friendship but agape seems more fitting for the type of love one has in perfect friendship, a love which is disinterested, self-giving and even self-sacrificing. Not surprisingly, Christ used this term to describe his love for us and the sort of love a Christian should show.

Agape is that purified love which is forged over time, getting to know one another through shared experiences, those ups and downs where you and your friend become one.

What International Friendship Day reminds us of is what really matters, and those are our relationships.

In a culture of hedonism, materialism and egoism, telling us we are nothing without our friends is a necessary reminder.

This is ancient wisdom as Aristotle knew well and so does one of the Bible’s wisdom books: “A faithful friend is a sturdy shelter: he that has found one has found a treasure. There is nothing so precious as a faithful friend, and no scales can measure his excellence. A faithful friend is an elixir of life; and those who fear the Lord will find him.”

Like what you’ve read? Consider supporting the work of Adamah by making a donation and help us keep exploring life’s big (and not so big) issues!

Anthony Stratford

Anthony Stratford is a newly qualified medical doctor and leader of a youth club in South London which helps young boys to become men of virtue and to serve God and society.